You might think you’ve read this story before. In a way, you have.

In part, it’s about a student of modest means pushed to his limits by his education. Challenged every step of the way, the student finds a place to flourish, rises to the top and then builds upon his experience to become a more well-rounded individual. In a sense, it sounds like a typical college success story.

Karin Hauffen is the student in question. A recent graduate of the James M. Hull College of Business, Hauffen is a shy, clumsy, good-natured giant of a man. He lives in Augusta, where he works remotely as a Dynamics AX Developer for eBECS North America, an Atlanta-based Microsoft partner. Like many young professionals, he is plagued by self-doubt, though, to meet him, you’d never guess it.

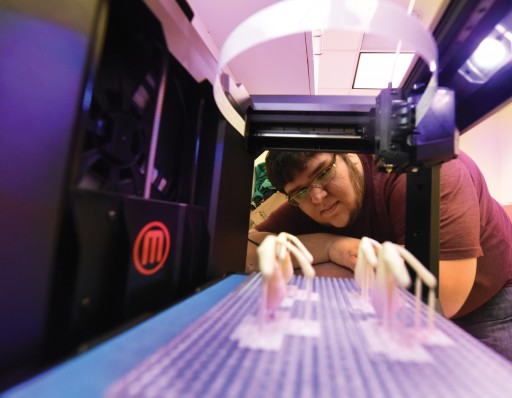

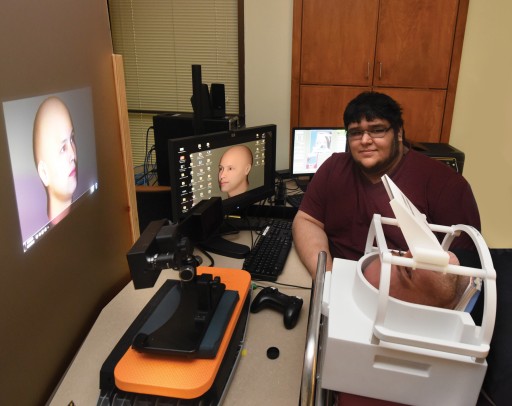

But despite his winning personality and admirable work ethic, no one can seem to nail down just how unique his achievements really are. Part of the problem is that he’s done a lot. On top of earning two associate’s degrees, certificates, a bachelor’s degree and landing a full-time job with a major software company, Hauffen is also the lead author on a research paper. The subject? Creating naturalistic 3-D objects for use in studying the perceptive capabilities of humans and macaques.

Impressive, sure, but still very familiar. On the surface, that’s what makes Hauffen’s story so remarkable: The fact that it’s almost unremarkable. He wasn’t remade by his professors, wasn’t reformed, reshaped or rebuilt by formal education. He didn’t become someone else. He grew.

And that’s where this familiar story takes a turn. Because there’s the part you’ve already heard, the part about a shy student who grew to become a more well-rounded individual, but there’s also the part you haven’t — the part about the university that grew, and prospered, alongside him. And that story is anything but typical.

A Place to Flourish

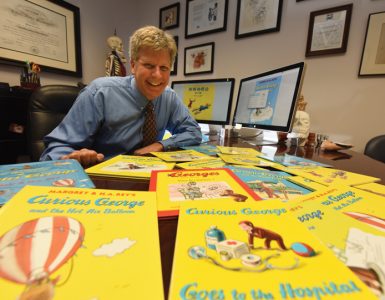

Dr. Jay Hegdé’s office is located on what is now Augusta University’s Health Sciences Campus, and the room contains the usual office fare: a gray desk, a gray phone and a variety of uncomfortable-looking rolling chairs. The space is austere, lit intermittently by sunlight filtered in through tinted shades or the dim glow of computer monitors. At the back of the room, however, nestled atop a long stretch of window sill, a handful of potted plants sunbathe in full view of the green space beyond.

It’s a curious juxtaposition. In a way, it’s also a mirror of the university’s promise: to provide a place of shelter, a place of learning where brilliance can flourish — both in and outside the lab. Such was the case with Hauffen, though, in hindsight, he refuses to call anything he accomplished here “brilliant.” It was all just — at least, he believed — what was expected of him.

That’s part of the magic of this story. Neither he nor the faculty who guided him want to take credit for his success. Somehow, that would cheapen the achievement. Instead, Hegdé puts it this way: “With Karin, we got to witness a clear evolution.” That evolution began in the spring of 2009.

Challenges

Now an assistant professor of ophthalmology, Hegdé first joined the Brain and Behavior Discovery Institute at the Medical College of Georgia in the fall of 2008. A specialist in the study of primate visual neuroscience and electrophysiological recording techniques in awake subjects, Hegdé quickly set about establishing new studies in his particular niche.

One of those studies focused on the relationship between neural activity and object perception. “This was a kind of novel research about how we see,” he explained. “A lot of it involves high-tech, computer-intensive things.

Part of the research involved developing a program to print naturalistic 3-D objects for testing the visual perception of macaques. By breaking these objects apart and distributing their fragments, he hoped to see if subjects could determine which object category the pieces belonged to on a better-than-chance basis. Normally, the task wouldn’t have been an issue. Programming is second nature to many researchers in the field. Had he wanted to, Hegdé could have easily written the code himself.

The issue wasn’t the amount of work, but rather the amount of time the work would take. “I knew I’d rather have an assistant do it so that I could supervise them while working on other aspects of the research,” he said. That left him with a problem.

Prior to consolidation, MCG didn’t have a computer science program. Student assistants and interns were sometimes called in to help with research, but the nearest candidates with programming experience were nearly three miles away at what was then Augusta State University. Without a formal pipeline between the two schools, finding those candidates was often difficult.

Hegdé, frustrated, turned his search elsewhere. After a time, he was introduced to John Arena, the former dean of Information and Engineering Technology at Augusta Technical College. After speaking through email, the two settled on a likely candidate, a student who had recently earned dual associate’s degrees in programming and e-commerce. That student, Hauffen recalls cheerfully, also happened to be in the middle of an intense job hunt.

“I was looking everywhere for work,” Hauffen said. “Around then, I heard Hegdé was looking for someone with my skill set. I was very nervous.”

And with good reason. Hauffen knew next to nothing about working in a lab. At the time, though, there was a shortage of tech-based opportunities in Augusta. Left with few other options, Hauffen applied. “We set up an interview by email,” Hegdé explained. “All I knew at the time was the name Karin Hauffen.”

A Germanic name meaning “pure,” Karin is traditionally feminine. The son of a Hispanic father and an Irish-German mother, Karin’s name is pronounced with a rolling Spanish “r” and, when pronounced correctly, sounds more like Ka-REEN or Ka-DEEN. Of course, on paper, his name looks like it would be pronounced Ka-REN. “My father mentioned he wanted to name me something unique,” Hauffen explained, chuckling. “He definitely succeeded.”

You can almost see where this is going, can’t you?

On the day of their meeting, Hegdé was expecting someone else when a brusque knock sounded at his door. When he answered, he said he was immediately taken aback. “Here I was expecting a woman and this big guy twice my size shows up,” Hegdé said, gesturing to represent the extreme height difference between them. “He’s a big dude.”

For his part, Hauffen said he remembers feeling a similar anxiety about their meeting, albeit for very different reasons. “I was nervous and intimidated, and it’s funny, because … I tower over him,” Hauffen said. “Researchers move between things almost like they have everything planned for the day. It was a process, learning my way around him.”

After moving beyond their initial shock, the pair quickly set to work hammering out the details of their new partnership. In so doing, Hauffen encountered the first of many challenges. “There were limitations involved with hiring Karin,” Hegdé said. Because he lacked a bachelor’s degree, hiring him and, more importantly, paying him what he was worth, proved challenging.

Hauffen was dismayed. His education had never felt like a problem before. After all, he understood the material. The things he didn’t already know, he would pick up quickly enough. He knew he could do it, because he always had before. “It fit my personality,” he explained. “I’ve always liked solving puzzles, figuring things out.” Knowing that, Hegdé took a chance on Hauffen.

“I hired the kid and told him you can come learn the programming stuff in my lab, but there is an actual programming job I need you to do,” he said. Despite a few other hiccups in the hiring process, the pair set up a contract. Soon after, Hauffen was on his way.

He worked from home at first, owing in part to the fact that he was already working two other jobs to support his family — one as a cook at Cracker Barrel and another as a freelance developer. Money was tight. When he worked in Hegdé’s office, he had to drive his family’s car to do so. Not fully aware of the constraints Hauffen was dealing with, Hegdé gave his new assistant upwards of three months to finish the project.

He was surprised, then, when Hauffen returned with it in just three weeks. “It was perfect,” Hegdé said.

Smiling, he added, “That was my first inkling that this was a really smart kid.”

A Student of Modest Means

The moment marked a pivotal change in Hauffen’s life. Having already seen him perform once, Hegdé set out to find new and more imaginative challenges for his new assistant to conquer. The first was overcoming his sense of self-doubt, a task which, Hegdé lamented, was too big for just the two of them. “I started giving him things he swore he had no business doing, no aptitude for, he was certain he was going to fail,” he said. “I would say, ‘Yeah, yeah, very nice. Now, go do it.’”

And Hauffen would. Time and again, he pushed himself to learn new material. Sometimes for the sake of programming. Other times, for the sake of research. The fruits of his labor soon paid off.

Within the first few months, he had taught himself MATLAB, a specialized programming language used in highly computational research. He learned the ins and outs of the lab and familiarized himself with the specialized equipment within. He even learned how to work with other people, a skill he said he’d never previously valued. And he learned to do it all flawlessly.

But as with all great stories, Hauffen’s successes were overshadowed by troubles. Though his educational evolution was well underway, his social journey was just beginning. Now a member of a large team at eBECS North America, Hauffen admits that he had some social “quirks” when he first started working for Hegdé.

“When Karin first started working for me he would take off his shoes in nonrestricted areas like the office,” Hegdé explained. “He was more comfortable that way; that was how he worked at home. I told him he would have to wear his shoes when he worked as a courtesy to his labmates.” Although Hauffen did so without question, the incident was only one of a handful of growing pains.

Another involved toilet humor. “He had a marketing course, I remember, and the professor wanted his students to learn to be good salespersons,” Hegdé recalled, detailing an incident very early in Hauffen’s undergraduate career. “He wanted the students to pick a product and pitch it to the class, a show and tell of sorts.” Karin, to his chagrin, chose to pitch toilet paper. It wasn’t a terribly surprising choice, though. At the time, Hegdé described his assistant’s sense of humor as that “of an overgrown boy.”

During lab time, Hauffen was engrossed in research related to depth perception. More specifically, he and his fellows were scanning eye movements to determine how patients move their heads to compensate for impaired vision, a condition known as parallax. Defined as the perceived displacement or difference of an object’s position when viewed along two separate lines of sight, parallax could be described as something seeming “out of place” from a certain point of view.

Despite his brilliance in the lab, that was precisely how Hauffen felt. His mannerisms, he felt, were something of a hindrance, though no one in the lab considered him so. But something else bothered him. Something he couldn’t quite put his finger on, though he’d experienced it before.

Rising to the Top

“In high school, I was all over the place,” Hauffen said.

A brilliant analytical thinker he always excelled at math and science. What really stuck with him, though, was his interest in computers. Before working in the lab, earning an advanced degree had never factored into the equation of his life. He said the reason he went to tech school in the first place was just to see if it was something he “wanted to dabble in.” But the more time he spent in the lab, the more he realized something was missing.

The people around him were all doctors. “Over my first couple of years as an employee, I was around people way more educated than me,” Hauffen said, breathing a sigh. “I think that was when I realized I really wanted to continue my education.” So, naturally, he did.

Shortly before the consolidation of ASU and Georgia Health Sciences University, Hauffen enrolled at the Hull College of Business. It was a tremendous decision. In retrospect, he said it was one of the best he’d ever made, though, at the time, returning to school was difficult. University life was trying, especially as a full-time student working two jobs. Balancing classes with newfound responsibilities soon became an almost daily struggle. Hauffen felt like he was underwater.

But that isn’t the Karin Hauffen Melissa Furman remembers. “When Karin came in, he immediately built relationships with academic advisors and was always very on top of planning what he wanted to do,” said Furman, assistant dean of the Hull College of Business. “When I think of Karin, I think of a very highly motivated, engaged student who was in charge of his own destiny.”

It’s not a statement Furman makes lightly. Prior to joining Hull and taking on the role of assistant dean, she worked for four years as a member of Augusta University Career Services, guiding students and recent graduates to careers in their given fields. As a result, she said she’s learned how to spot a certain class of students. “In the college, I meet people, sometimes freshmen and sophomores, who I know are presumed super stars,” she explained. “These are students who I know are going to make it, who I invest in and try to mentor. He was a presumed super star.”

Classes at Hull transformed Hauffen. Or rather, they transformed his self-perception. “When I first started, I was also balancing two jobs, so it was a little bit stressful,” he said. “People like Dr. Todd Schultz and Melissa, they made me more excited about choosing my degree. Working with them made me feel like I’d made a good choice.”

From Furman’s point of view, it was certainly the right choice. “He was featured on our website, in our newsletters,” Furman said. “He was a Hull Scholar, an ADP Scholar, a Pamplin Scholar; Karin was sort of our ‘go-to’ success story.”

Suddenly, the shy lab assistant with the “boyish” sense of humor was making a name for himself. He started moving away from his more “childlike” tendencies and began focusing more on his professional prospects, chasing scholarships and internships — any and every accolade he could achieve to further his budding career as a developer.

And once it started growing, that list of accomplishments went on seemingly without end. “He received so much scholarship money, he kind of maxed out,” Furman explained. “There were scholarships he was actually awarded that he couldn’t accept because he’d maxed out the amount of money he could receive from a financial aid perspective.”

Today, he says he’s thankful for the experience. Thankful, and a little sleepy. “I think having so much on my plate actually helped me in the long run,” he said with a grin. “It made me appreciate sleep when I graduated, though. I had to catch up on four years of sleep.

A More Well-Rounded University

In Hauffen, two separate educations — two points of view — intersected. The Medical College of Georgia made him a stronger programmer and a better researcher. At the same time, Augusta State University and Hull were making him a better professional.

Today, on either campus, the Karin Hauffen who first arrived at Augusta University is nearly unrecognizable. Though he’s still the same good-natured giant, he’s somehow different, now. He holds his head a little higher. His wit, once boyish, is now dry and charming. And while he still indulges in the occasional shoeless telecommute session, he cuts a dashing figure in a suit.

When I think of Karin, I think of a very highly motivated, engaged student who was in charge of his own destiny.

– Melissa Furman

He’s a well-rounded student — the kind of alumnus universities hope for. That said, no one on either campus will claim responsibility for his success. “I think inside he knew he was worth that much,” Furman said. “He just needed the reinforcement of people telling him, ‘You’re amazing.’ That was a proud moment for me, when he finally realized his worth.”

Likewise, Hegdé believes Hauffen owes it all to himself. “This kid has everything going for him,” Hegdé said. “I keep telling him, ‘if you don’t be your bonehead self, keep your nose clean and keep doing everything you’re doing, then the sky is the limit.”

Predictably, though, Hauffen won’t claim responsibility for it either. In his mind, his accomplishments run tangentially to his own efforts, the former and the latter related, though, perhaps, not correlated. Some things never change. “I owe Augusta University so much, not just for helping me grow up a little bit and being more mature, but also for making it to where I am now,” Hauffen said. “I had no idea I was ever going to go this route, but I’m so glad I did.”

Regardless of who is responsible for Hauffen’s growth, though, it’s clear that his story could only have happened where it did, in a place where two equal parts combined to form a much greater whole. “As a consolidated university, we now have the potential for a lot more kids like Karin,” Hegdé said. “Kids for whom various kinds of internships or research experiences or other kinds of work experience would make a huge difference. We are a much better place now for developing students like Karin in the future.”

That is the ultimate takeaway from Hauffen’s story. Because from the very beginning, the story was never solely his. Along every step of the way, the schools that would become Augusta University were playing a role, too. A role that has now consolidated opportunities for a new generation of students.

And that makes this story anything but typical.