Exploring the Impact of Two New Antibodies on Myasthenia Gravis

Riding the familiar roads of north Georgia’s Franklin County, Kim Roach is comfortable and happy.

But in the trunk of the car is a walker the 52-year-old now needs to steady herself. The flowerbed in front of the family homestead she shares with husband Marvin and their two dogs has weeds, and while her house is neat, it is not truly clean, at least by her exacting standards.

It was about three years ago that the generalized fatigue set in, as unfamiliar a presence in her life as the weeds now in her garden. She had always been a doer, working a full-time job, raising four children, now playing with four grandchildren, and helping Marvin tend to a farm that housed 80,000 chickens. She was always his extra set of hands, up before sunrise and slowing down maybe by 9 p.m. She reasoned she was still too young for age to be cutting her energy, but had no idea what it might be.

“I was just always brought up, you keep on going,” says Roach, whose parents are still following their own advice well into their 70s. But soon, even her voice was giving out by early afternoon, with some slurring of her words and hoarseness. And she was getting weaker. “I would be picking up things, and I would just drop them. I wouldn’t be able to open simple jars. That has never been me.” Her shoulders, forearms and neck would give out just drying her short, gray hair.

A series of doctor visits followed. Maybe she was pushing herself too hard, but she always had. Maybe it was arthritis, but there was no evidence of it. Maybe it was fibromyalgia. Roach seems to have ample patience, but not when she thinks people, including physicians, are wasting her time. “I would rather you tell me you don’t know what is going on,” she says.

Her increasing symptoms finally brought her to Athens neurologist Dr. Edward S. Novey. And, what he told her made her also have trouble breathing: She likely had either amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) or myasthenia gravis. Roach really didn’t know much about myasthenia gravis, but she reasoned it could not be worse than having ALS.

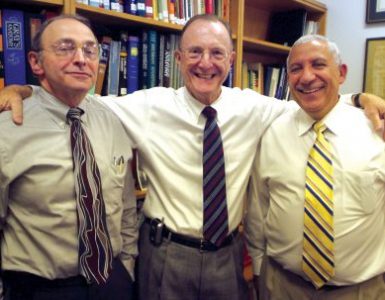

Novey called Dr. Michael H. Rivner, a Medical College of Georgia neurologist specializing in neuromuscular disease, who directs the Electrodiagnostic Medicine Laboratory at Augusta University Medical Center. He saw her classic disease symptoms, and the electrical studies showed signs of troubled muscle fibers. But in her blood, Rivner found no evidence of the two antibodies known to attack the juncture where nerves and muscles connect and to cause myasthenia gravis.

But, there were antibodies to something called LRP4.

Now Roach is among more than 600 patients from 22 myasthenia gravis centers across the nation whose blood and symptoms could further refine the diagnosis and treatment of their disease.

An uncommon problem with a less-common twist

Myasthenia gravis, a relatively uncommon problem, is among the some 40 conditions classified as muscular dystrophy. Roach was experiencing many of its classic symptoms as the strong muscles she once controlled weakened and the effect seemed to spread through her body.

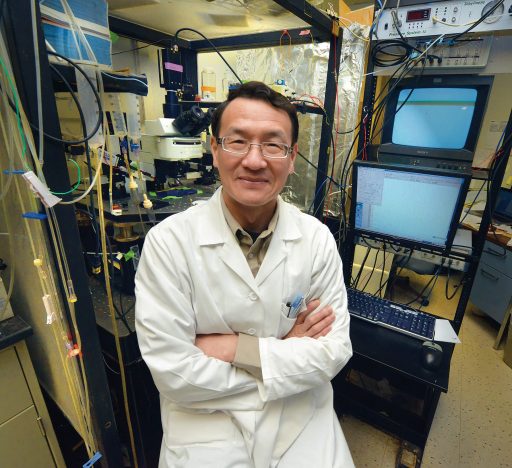

“The problem with this disease is the brain and body and muscles don’t communicate, at least not correctly,” Dr. Lin Mei, chairman of the MCG Department of Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine and Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar in Neuroscience, says of a communication network that never sleeps even in a state of stillness.

With myasthenia gravis, the body inexplicably begins to make antibodies that affect essential communication between brain and muscle. By far, the most common antibody found in patients is for the receptor for acetylcholine, a chemical released by neurons to activate muscle cell receptors. The other is an antibody to MuSK, an enzyme that supports the clustering of these receptors on the surface of muscle cells. Fewer receptors clearly lessen communication between brain and muscle. What else might be happening began to come together in 2008, when Mei’s lab found a missing piece of the puzzle of how neurons and muscle cells establish lifelong communication.

Essential communication under attack

During development, agrin is a protein that motor neurons release to direct construction of the nerve-muscle juncture. MuSK, one of the known targets in myasthenia gravis that sits on the muscle cell surface, initiates critical internal cell talk so synapses, or connections, can form and receptors that enable specific commands will cluster at just the right spot. The conundrum was that agrin and MuSK don’t directly communicate, explains Mei.

Much as one friend might get two other friends together, his lab found that agrin starts talking with LRP4, a protein also on the muscle cell surface, then recruits MuSK to join the conversation. LRP4 and MuSK enable formation of the synapse, where the nerve reaches out to the muscle cell and where acetylcholine receptors must cluster for communication to happen during development and lifelong, Mei says.

He found the link between agrin and LRP4 in 2008. He reported finding LRP4 antibodies in patients’ blood in 2012 then went back to the lab and reproduced disease symptoms by giving the antibody to mice the next year. He identified agrin antibodies as a possible disease cause in 2014.

Now, Mei is prinicipal investigator on a $3 million grant from the National Institutes of Health that has him and Rivner looking further at both patients and mice to try to determine how common these newly found antibodies are, the specific damage they do and if new treatments also are in order to stop it.

“This will help us understand a new cause for myasthenia gravis,” says study co-investigator Rivner. “We want to know how prevalent these patients are.” He and Mei also want to know whether the double-negative patients who have the new antibodies also have unique symptoms. Rivner notes that patients with MuSK and acetylcholine antibodies may.

“We want to know whether these patients have any unique symptoms so we can diagnose them early then confirm their diagnosis with a blood test,” Mei says. Electrical studies of how nerves react as well as antibody results are pieces of the puzzle physicians currently put together to make a diagnosis, although technically, patients don’t have the disease until they have the symptoms.

Rivner says having a routine blood test for patients like Roach would definitely help everyone feel more certain about the diagnosis. Mei notes that several companies already are interested in developing agrin and LRP4 antibody tests, which would not have been available to Roach without the collaborative research of Mei and Rivner.

“These patients also may very well have slightly different symptoms because of where the antibodies are acting. We don’t know that yet until we analyze these patients,” says Rivner, who follows about 250 patients with myasthenia gravis. About 30 of his patients, including Roach, are currently considered “double negative,” and there are probably close to 900 across the country, he says.

In mice and men

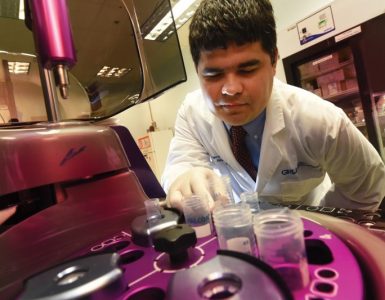

Over the next five years, many of those patients are having their blood tested for the two new antibodies. Similar studies will be done on the blood of healthy individuals as well as patients with other neurological problems such as Alzheimer’s and stroke. These tests on other neurological problems will help ensure that the antibodies’ presence is not random but, instead, is causative in myasthenia gravis, so researchers can begin to collect evidence about whether they also contribute to other maladies, Mei says. Controls will help further tie their presence to myasthenia gravis.

Mice, rabbits and other animals immunized to produce LRP4 antibodies also show classic signs of myasthenia gravis and tend to be less active, although they can survive for long periods, Mei says. Their electrical studies also paint a poor communication picture, which Mei likens to a bad personal relationship. “When there is no communication, things don’t go well,” he says. When they later examine the neuromuscular junction, the researchers can see the disentegration.

They are continuing some of the animal studies to learn more about how both antibodies do their damage. Are they directly interfering with the signal between brain and muscle, less directly interfering by attracting macrophages to chew up the neuromuscular junction, or both? Mei asks. These kind of details will help identify a strategy to stop whatever they are doing. They also are looking at whether the human antibodies they are collecting in patients attack the neuromuscular junction in mice that cannot generate antibodies.

Back in north Georgia, the expansive chicken houses on a sprawling 25 acres were idle for the first time this winter. Roach acknowledges that many of her fellow chicken farmers regularly take the cold north Georgia winters off, but this was a first for her and Marvin. Everything is just harder in the winter, she says, perhaps more so this winter. Much like herself, she wonders if those houses will – or can – ever bustle again. She just can’t help Marvin like she used to.

The prednisone she takes as part of her treatment regimen, likely coupled with her dramatically reduced activity, means she has gained weight, which further contributes to her troubles getting around. “It’s very frustrating.” At the time of this interview, she had experienced three pelvic fractures, which she suspects are also from the prednisone that is now part of her daily life, and was just recovering from a fractured left wrist.

Still, there is much joy and hope in the life of this woman, especially those days when the grandchildren come calling and as she enjoys lunch at a local spot where every third customer – and the owner – seem to know her so well.

Missing are signs of anger at a disease that is nipping away at a fundmental communication in her body.

“I just have to trust God every day, and I ask him every day before I ever hit the floor just to give me the strength to get up. I ask him to give me a good attitude, a kind spirit toward everybody and not to let me take out my frustrations with what is happening to my body on everybody else.”

Today’s Treatment

Most myasthenia gravis patients’ symptoms tend to respond well to therapy, which typically includes chronic use of drugs that suppress the immune response, Rivner says. However, immunosuppressive drugs carry significant risk, including infection, cancer and weight gain. In particular, patients with the outlier antibodies may need a different approach.

Removal of the thymus — a sort of classroom where directors of the immune response, called T cells, learn early in life what to attack and what to ignore — is another common therapy for myasthenia gravis. While the gland usually atrophies in adults, patients with myasthenia gravis tend to have enlarged glands. Rivner is part of another NIH-funded study to determine whether gland removal really benefits patients. Other therapies include a plasma exchange for acutely ill patients.