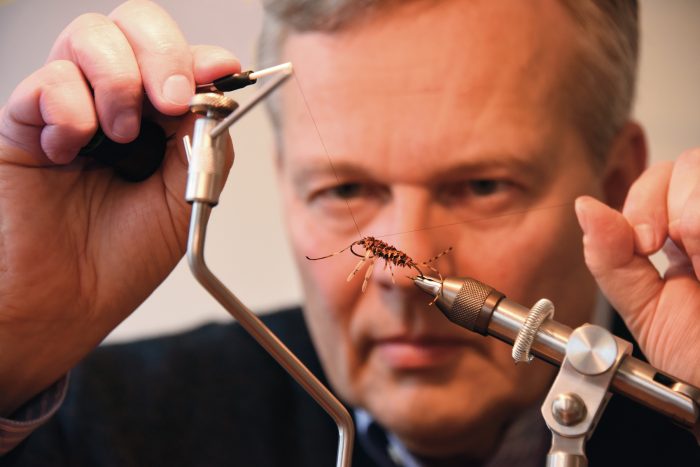

Dr. Steffen Meiler, chairman of Anesthesia and Perioperative Medicine, is pushing the envelope — and it’s paying off

Dr. Steffen Meiler only got about two hours of sleep the previous night.

But you wouldn’t know it. A self-professed workaholic, Meiler is still as enthusiastic and curious as he must have been as a young boy in Frankfurt, Germany, when he first made the decision to go into medicine. “I just get up in the morning, and I’m ready to go,” he says.

As chairman of the Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine at the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, he has a lot on his plate. Meiler still maintains an active research lab, and his most recent National Institutes of Health-funded project is continuing his significant, decade-long work into sickle cell disease. He sees patients, complex airway cases in particular, once a week. And since he was tapped as chair, he’s been focused on bringing his collaborative research approach to the clinical and administrative sides of the department.

Driven? Most definitely.

Pushing the Envelope

An avid reader, Meiler was about 12 years old when he first picked up a diary of Albert Schweitzer’s groundbreaking expedition to Africa. The adventurous story of the physician, organist, theologian and Nobel laureate who built the first modern hospital in the heart of the Dark Continent at the beginning of the last century spellbound him and cemented his resolve to go into medicine, following in the footsteps of his internist father, Dr. Günter Meiler.

The elder Meiler eventually took on the role of medical director for the German office of Nationwide insurance company, and the young Steffen would often rub shoulders with Americans in the medical field. So by the time he entered medical school, political unrest on German university campuses made it an easy decision to try something different, and he studied abroad for a year at The Ohio State University College of Medicine.

He enjoyed the experience and the approach of American teaching methods so much that he dashed off a letter to the dean of his German medical school. “I still see myself sitting in my mother’s office in front of the typewriter, typing about a 25-page letter … providing a comparison on how we conducted teaching and how we constructed the educational environment at medical school in Frankfurt versus what was in the U.S.,” says Meiler. He pauses and adds with a smile, “It’s fortunate I never heard back.”

But it wasn’t the first time Meiler pushed the envelope — and it wouldn’t be the last. After graduating from the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University School of Medicine in Frankfurt, Meiler completed residencies in internal medicine and anesthesiology at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, along with a critical care fellowship and two research fellowships in molecular genetics and gene therapy at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School. There, he joined Harvard’s first large-scale genetic screen of the zebrafish as a vertebrate model to study the genetic decision points in the development of the cardiovascular system.

Meiler had a theory that tracking down one of the chemically induced mutations that leads to a poorly contracting heart in one of the fish families could provide insight to the genetic origins of human cardiomyopathies. His mentor, the noted researcher and clinician Dr. Mark Fishman, told him bluntly, “Don’t do it.”

“It was a high-risk undertaking, and if I had invested all these years of genetic research with no significant results at the end — say it turned out to be a simple housekeeping gene — it could have curtailed my scientific career,” Meiler says. “But I had a gut instinct that this would work out.”

It took pushing the envelope — plus years of research — but Meiler was one of the lead authors of a team that would go on to identify a cardiac-specific mutation in the largest-known protein, titin. This work would lead to the first report of a titin mutation being linked to heart failure in a vertebrate heart, but titin would go on to be identified as having the largest group of mutations leading to cardiomyopathy in humans. It’s a vast understatement, but “it ended up being a fairly significant scientific contribution,” says Meiler.

Southern Exposure

Southern Exposure

By 2002, new opportunities arose. Meiler could have continued a highly satisfying career as a researcher and clinician in Boston, but Dr. David Stern, then dean of Georgia’s public medical school, came calling. He wanted a vice chair for research in anesthesiology, and he wanted Meiler. And Meiler relished the chance to build something special.

Soon after he came South, Meiler quickly became close friends with Dr. Abdullah Kutlar, director of the university’s Sickle Cell Center. Even as Meiler was forming relationships regionally and nationally — resulting in the building of three NIH-funded research programs in the department and approximately a million dollars in annual NIH funding in just a decade — he was also transitioning his interest in genetic diseases from the heart to sickle cell disease. “When you embark on a research theme, one of the things I’ve observed is that the environment has to be right, with the resources as well as the expertise available to work collaboratively,” he says. “That was the case in sickle cell disease since MCG had a very proud, long and strong history in sickle cell.”

According to Meiler, the disease is in many ways ideal for genetic research. Patients with the inherited red blood cell disorder have two abnormal hemoglobin genes, hemoglobin SS, that cause red blood cells to form a stiff, sickle shape, reducing oxygen delivery and impeding blood flow. Meiler’s collaborative work with the NIH-funded Nanomedicine Center for Nuclear Protein Machines, led by the Georgia Institute of Technology, focused on the development of a gene correction technology platform for the sickle cell mutation. This approach relies on the ability of gene correction reagents to enter a sickle cell patient’s own hematopoietic stem cells, make it across the difficult barrier of the nuclear envelope and find the genomic address of the ß-globin sickle mutation. The reagents would then induce a DNA double-strand break nearby and use the cell’s own repair machinery to synthesize a normal, mutation-free stretch of DNA across the break-site from a template of wild-type DNA.

Fast forward 10 years later to 2015, and it could be argued that what Meiler achieved for the heart, he and his collaborators have now achieved for sickle cell disease. It’s not a cure yet, but Meiler and investigators from centers nationwide have now developed a proof of concept for the gene correction platform that allows researchers to repair the site of sickle mutations in approximately 10 to 30 percent of human hematopoietic stem cells. These bench results will now provide the basis for the planning of a gene correction trial in adult patients with sickle cell disease.

Meiler’s own work in sickle cell is also continuing. This includes a recent $8.4 million grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute examining the role of endothelin-1 in acute lung injury, kidney injury and pain in sickle cell disease with his colleagues and co-principal investigators, Drs. Kutlar and David Pollock, former chief of the MCG Section of Experimental Medicine and now director of Cardio-Renal Physiology and Medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine. Sickle cell patients often experience episodes of acute pain, and at the same time, they have elevations in the level of endothelin-1. Using mouse models, the researchers have already found that by blocking the endothelin A receptor, pain is abolished, and kidney and acute lung injury is significantly ameliorated. “We have absolutely amazing data on every single front,” says Meiler. “We’re really excited about this.”

Tapped for Chairmanship

Even as Meiler continues his enthusiasm for research, he’s also applying his research acumen to his entire department. Just as he advised his research team, he’s encouraging his staff and residents to build relationships both internally and with colleagues nationally and to learn from one another, regardless of rank and title. He likes to compare his specialty to a team sport. “It’s a culture change, but one that will create unlimited opportunities,” he says. “We want to build a department of anesthesia without borders both on our campus and in how we relate with others in the medical profession.”

And just as he’s learned over the years to ask the right questions in research, he wants his department also to consider how to frame the right questions, how to implement smart solutions, how to minimize waste and continually improve the educational and patient care environment. Training is also important — and not just for leadership. Meiler is making training in leadership and process improvement skills available to his entire department. “That’s important if you want to build effective, tightly integrated and knowledgeable teams,” he says.

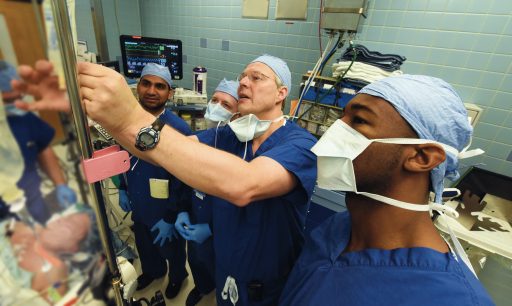

It’s easy for most to think of anesthesiology as simply “putting someone under,” but ultimately, Meiler’s goal is to increase the value of the department of anesthesiology to the medical school and its teaching hospitals by expanding its activities outside of the operating room into the perioperative care area. “Taking our patients safely from induction to emergence is at the very core of what we do, but our expertise goes so much further,” he says. “In addition to our clinical expertise in critical care and pain management, there is tremendous opportunity for us to be involved in the creation of coordinated care delivery systems and best-practice clinical pathways with our colleagues from surgery and other services to improve the outcome and to lower the cost of care for our surgical patients. The build-out of the perioperative surgical home, a highly collaborative, multidepartment effort that seamlessly integrates patient care before, during and after surgery and even post-discharge, is one great example of this type of opportunity.”

There are many other projects he’s tackling — including the launch of simulation training at the J. Harold Harrison, M.D. Education Commons to provide every anesthesiology resident with approximately 100 hours of training, as well as a telemedicine ICU to support 24/7 coverage thanks to the health system’s 15-year alliance with Royal Philips to provide advanced medical technologies and services — and Meiler is relishing every moment. As he has throughout his career.

“It’s about being in the right place at the right time,” he says. “I do believe if you have passion for something, you send out signals into this world that will eventually be answered with a coalition of supportive people and enabling circumstances.”

Meiler at a Glance

- Alumnus of Johann Wolfgang Goethe University in Frankfurt, Germany

- Research fellowship, Heart Failure Laboratory at The Ohio State University

- Internal medicine internship n Internal medicine residency

- Anesthesiology residency at University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics

- Critical care medicine fellowship n Research fellowship in molecular genetics/associate member, Developmental Biology Laboratory n Research fellowship in gene therapy/associate member, Program in Cardiovascular Gene Therapy at Cardiovascular Research Center, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School

- Executive Committee Member, National Institutes of Health Nanomedicine Center for Nucleoprotein Machines (NIH/NEI 1 PN2 EY018244-06) n Reviewer for Blood, British Journal of Haematology, Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, Journal of Proteome Research, Anesthesiology, Vascular Pharmacology and Journal of Clinical Anesthesia

- Top Doctor, International Association of Anesthesiologists