Vein of Galen

It’s a plum-sized sac inside a baby’s brain, taking away critical lifeblood, but an endovascular approach for this vein of Galen malformation gives these tiny patients a fighting chance.

The beautiful babble that freely streams from 9-month-old Maiah Byars almost didn’t.

She entered the world with this perfect little 6-pound exterior, enviable skin and dark eyes that captivate so you just have to believe whatever it is she is trying to tell you.

But the biological monster inside her head was killing her.

Making the monster

During development, the brain needs a lot of blood and oxygen, even compared to other developing tissues and organs. That means a lot of blood vessels as well as stem cells that are needed during development become irrelevant, even dangerous at birth.

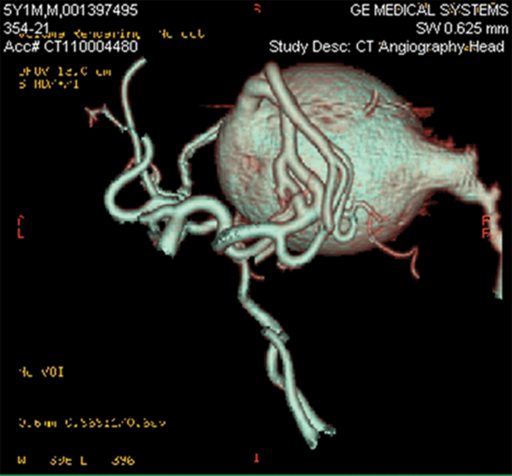

One of those vessels, the median prosencephalic vein – the precursor for the vein of Galen – likely helps drain that large volume of blood during development, then shrinks away as the baby reaches term. In rare cases like Maiah’s, an abnormal and direct connection between a high-volume artery and this vein inexplicably develops. After birth, the still-developing brain continues to crave plenty of blood, oxygen and nutrients, and the odd coupling persists, becoming a highly lethal liability.

In the small architecture of a baby brain, this vein of Galen malformation can become the size of a plum, taking up space in the still developing center of intellect. It almost looks innocent on ultrasound, like a tadpole or even another fetus in the middle of her brain, just above the ear. In Maiah, the tadpole should have dissolved before mom Ashley and dad Donell Brown ever saw their baby. Instead it was sucking the blood away from Maiah’s heart and other organs.

“If it doesn’t disappear, it recruits arterial flow and becomes this big sac,” says Dr. Cargill H. Alleyne Jr., endovascular neurosurgeon and chairman of the Department of Neurosurgery at the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University.

“We don’t know why it persists in some people. We think it’s probably just a remnant.”

The malformation recruits feeder blood vessels in tumor-like fashion, setting up a vicious cycle as blood intended for the brain keeps getting drawn into the enlarging sac then directed right back to the heart. “It’s almost like a vacuum,” says Alleyne. Tiny brain vasculature should instead be delivering blood to the neurons and astrocytes, the brain cells that support neurons, by providing them the blood, oxygen and nutrition they need. Instead, the small vessels shrink from lack of use.

The heart persists but works too hard and in vain. “The heart is just pumping and pumping faster,” Alleyne says, trying to do its vital job of supplying the brain and other organs and tissues with blood. It takes a toll, as young hearts soon become like old ones, which are riddled with disease, with enlarged pumping chambers from working so hard. Babies like Maiah can end up taking some of the same drugs as these older patients, like Lasix, to try to take some pressure off. Ultimately, the brain does not get enough blood; nothing does.

The distinctive sound, called a bruit, of fast-moving blood is sometimes audible without a stethoscope and is one way the condition is first detected. Late pregnancy ultrasound is another. Sometimes it’s the fact that babies are in heart failure.

IN VEIN

IN VEIN

The vein of Galen is named for Aelius Galenus, a Greek physician and surgeon in the Roman Empire, who made significant contributions to understanding pathology as well as the circulatory system, including recognition of the distinctive colors of venous and arterial blood. He turned out to be off a bit in theorizing that there were two separate, one-way networks carrying the fluid staff of life rather than an interconnected system. Galen would also discover one of the large blood vessels that drains the brain during development, which now bears his name. The condition associated with the vein of Galen is a bit of a misnomer since it’s actually the median prosencephalic vein — which comes right before it in the circulatory line — that balloons in the brains of babies like Maiah. While rare, the vein of Galen malformation accounts for about one-third of the vascular malformations in the brain diagnosed in children. Smaller malformations may not be detected early on and may not require treatment.

Heart failure, hydrocephalus, strokes, seizures, mental retardation, even a form of starvation can result as this abnormal connection monopolizes the lifeblood of the baby. Damage can be multiplied by the size of the growing sac that can put pressure on other areas of the still-developing brain. At least in this scenario, the also still-forming skull is not a solid mass so provides some flexibility for the abnormally shifting brain.

A mesh malformation

Alleyne vividly recalls a picture he has seen where the tissue of the brain had been melted away to reveal the complex micro- and macro-architecture of its vascular system.

No doubt fascinated by what he considers the body’s last great frontier, the brain’s essential vasculature also captivated him as a resident and would lead him to an open vascular and endovascular fellowship.

“It looks like a mesh,” he says. Within this mesh, large arteries are not supposed to directly fill the median prosencephalic vein, or any vein for that matter, but rather filter down into smaller and smaller vessels and to microscopic capillaries. After capillaries have fed the brain cells, they should give the now low-pressure and high waste-product blood back to thin-walled veins. The process starts anew with progressively bigger veins that deliver blood back to the heart and lungs. While Alleyne specializes in a wide variety of problems with the vasculature, including aneurysms and arteriovenous malformations – a more widely recognized irregular connection between artery and vein – he may see only one or two vein of Galen malformations each year, which affect male and female children equally.

Before endovascular approaches were possible, open surgery to access the malformation and clip it to block blood flow were highly risky, taking babies with large malformations from essentially a 100 percent chance of dying to maybe a 90 percent mortality rate. Suddenly, there would be a lot of blood with no place to go except the shriveled blood vessels that were unaccustomed to it. Massive hemorrhage was frequent and almost immediate. “Most patients died when you tried to operate on them,” Alleyne says.

Today, it’s still a risky scenario, with slightly better than a 50-50 chance of survival. But the 100 percent chance of dying without intervention has not waivered in babies like Maiah, who spent the first three months of her life in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Children’s Hospital of Georgia.

Now Alleyne slowly shuts down the malformation’s powerful operation. “You don’t want to shut if off suddenly,” he says, thinking again of the collateral damage from the blood suddenly seeking someplace else to go. “You want a slow clotting off of the sac,” or there might be a bleed in the brain as nearby arteries, which have been starved for blood flow, rapidly overfill.

He typically enters through the palpable femoral artery at the groin, works his way to the aorta and past the heart, into the carotids and the vertebral artery in the neck, and to the mouth of the monster. An angiogram is his map and a tiny wire threaded through a progressively smaller catheter his lead.

“Sometimes your plan is to get into that sac and start packing it off,” Alleyne says. Tiny coils, which he carries in the pocket of his white coat to show patients and families, are used to fill the sac — in Maiah’s case, over three separate sessions. A glue that hardens when it hits blood helps close off the feeder vessels the sac recruited.

Epilogue

Their second child entered their world distinctly different from her now 4-year-old big brother Amari. Maiah wouldn’t eat, only sleep, says Byars of those first couple of days at Doctor’s Hospital, a Hospital Corporation of America facility in Augusta. Her breathing was a little fast, her heart rate a little “different,” the mother recollects. The baby was transferred to Children’s Hospital of Georgia. When she could join her baby there, the young mother — whose family has thankfully spent little time at hospitals — realized something was very wrong with Maiah.

“It was overwhelming,” she says. Her baby was rapidly deteriorating, her organs failing. While even the thought of a brain procedure with a 50-50 survival rate was tough, the 100 percent mortality rate without it was unbearable.

Nine months later, an ultrasound found the flow to and from the malformation in Maiah’s brain greatly decreased; her organs were no longer failing; and her brain surgeon was optimistic that the monster would finally and quietly make its exit.

“She is basically a normal kid now,” says Alleyne, who will follow her for the next couple of years with ultrasound and other measures to ensure that the flow continues to trickle and eventually subside.

These days find Maiah getting used to her first bottom teeth, eating baby food, pulling big brother’s hair and babbling intently to visitors.

About Alleyne

Alleyne went to medical school at Yale University, completed his neurosurgery residency at Emory University, and a cerebrovascular and skull base surgery fellowship at Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix. He completed an endovascular fellow-ship at the University of Rochester while on the faculty there. Alleyne joined the MCG Department of Neurosurgery in 2004 and was named chairman in 2007. He directs the Neurosurgery Vascular Service at Augusta University Health and is the Marshall B. Allen Jr. Distinguished Chair of Neurosurgery at the medical school. The MCG Department of Neurosurgery he leads just turned 60 years old. Its first chief was the late Dr. George Smith, who invented a smart drill that stops before it hit brain tissue, as well as an early aneurysm clip.