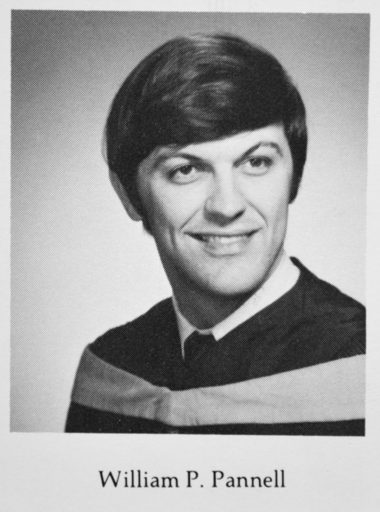

When Dr. Bill Pannell said he wanted to practice surgery in his tiny hometown, many were skeptical. But he’s not only built a strong practice — he’s given back, developing a national program to train surgery residents.

Dr. Bill Pannell jokes that he was raised by the entire town of Cordele, the tiny town in southwest Georgia – population 11,000 – otherwise known as the Watermelon Capitol of the World.

“When I first started practicing, I had a young lady working with me, and she stopped me one day to say, ‘I’ve got another patient who says she raised you. Just how many people did raise you?’” the Cordele surgeon and 1972 MCG graduate remembers her asking. “I told her, ‘Everyone that says they did.’”

While it may be a slight exaggeration, he knows his life could have turned out very differently without those who did pitch in.

At age 6, Pannell found himself scared and alone, riding a bus the 100 or so miles from his home in Columbus, Georgia, to Cordele. Even at this early age, he had found himself estranged from both parents, and he spent the two-hour ride just hoping and praying that his grandmother Mary Pannell could take him in. Nothing was certain. She had just suffered a heart attack six months before.

“I was scared to death of what would happen if I couldn’t stay – an orphanage or foster home? For two or three days [after I got there], I clung to her like crazy. I slept in the same bed with her,” he remembers. “I came home one day after school and she was at a neighbor’s house and no one was home. I panicked. When she finally got home, I was crying and carrying on. She looked me in the eye and promised, ‘I’m going to raise you.’”

Pannell’s mother was killed in a car accident two months after he arrived in Cordele.

He says his grandmother had already raised seven children as a single, widowed mother through the Great Depression and her already grown children weren’t sure she could handle raising her grandson, too. But she wouldn’t hear it.

She knew she wasn’t going to do it alone.

“I could walk from one side of this town to the other, no problem. It was an environment where you know most of the people, they know you and everyone’s looking out for you,” he says of his hometown. “I was scared to death, and I walked into my grandmother’s arms and right into this community’s arms. It just fit. I just flourished. I had a wonderful childhood.”

Childhood turned to young adulthood, and that scared boy from Columbus eventually found himself at Auburn University on an NROTC scholarship from the United States Navy with dreams of being an English teacher and a high school football coach. He walked on to Auburn’s football team and says he quickly realized he “was not the caliber of football player that would succeed at that level. A late-night conversation with a football coach also made me realize the coaching business was perilous, to say the least.”

It didn’t quite fit.

That spring had also turned into a tumultuous time for his family – an uncle who had been a father figure to him died suddenly. His estranged father died.

Mary had also suffered a heart attack and passed away.

It was time to go home.

He came back to southwest Georgia and enrolled at Valdosta State Univer-sity, using the social security benefits he qualified for after his father’s death to pay for his tuition. There his adviser, Dr. James Connell, then chair of the biology department, talked him into majoring in science. Pannell moved forward, thinking that he would still be a teacher – just in science, instead of English.

Caught up in the social unrest of the ‘60s and in “the fury of young idealism,” Pannell became president of the Student Government Association and fancied becoming a politician. But Connell warned him that route was “just as perilous as being a coach” and suggested he consider medical school instead. He took the MCAT and used his last $25 to pay the application fee for MCG. By that December, he was accepted to the state’s medical school.

“I always loved being a student. I loved going to school,” he says. “People always ask me why did you go to medical school? Why did you want to be a doctor? You can say all these flowery things, but I think you have to really want to be a student – a lifelong learner. The rest of your life you have to want to read and learn.”

Pannell arrived at MCG in 1968, and he already knew what kind of doctor he wanted to be. He simply had to think back to his small-town upbringing and the old-fashioned family doctors he’d grown up admiring – the ones who’d done everything from basic care to surgery; the ones who treated the pregnant women, delivered their babies and became their child’s doctor; the ones who treated his beloved grandmother; and the ones who treated him and never sent a bill.

Of course there was no question about where he was eventually going to practice.

“All throughout medical school, I was introduced as ‘That’s Bill Pannell, and he’s going back to Cordele,’” he says, laughing. He says he knew he would wind up back home and he knew he’d be a surgeon. “Medicine had become incredibly specialized, and family medicine physicians were no longer doing surgeries, delivering babies and what not. I wanted to be able to take care of the patients here if I could and not ship them off somewhere else. General surgery provided the best avenue for that.”

After graduation, Pannell again found himself in a big city that didn’t fit when he traveled to the University of South Florida and Tampa General Hospital for his surgery residency. He says he couldn’t wait to get back home to open up his surgery practice at Crisp Regional Medical Center, his small hometown hospital, which at the time was just a space that served as the operating room and emergency room and a handful of patient rooms.

That didn’t matter to him. He’d spent nine years in big cities during medical school and residency that just didn’t fit – but his 11,000-population hometown did, to many people’s amazement.

In fact, while sitting for his interview with a committee of the American College of Surgeons, a member looked at Pannell and asked a simple question: Why did a board-certified general surgeon want to go back to tiny Cordele? Pannell couldn’t answer him.

“I stumbled over some stuff about it being my hometown and wanting to be like the doctors I knew growing up, but I didn’t give them a decent answer,” he says. “One turned to me and said ‘You’re going to starve to death down there.’ Another one turned to him and said, ‘No, he’s going to start his own little teaching center down there.’ Everyone got a big laugh out of that.”

Turns out, they shouldn’t have been laughing.

Shortly after returning home, Pannell began offering surgery rotations to students from his alma mater. He also began working with Dr. Don Nakayama, a Macon surgeon, who had been sending surgical residents to Cordele. They both repeatedly found that residents nearing the end of their five-year training weren’t always ready to operate with minimal supervision, much less alone. The fact that they weren’t board-certified also created liability issues for hospitals if they did.

Pannell had a solution. He created the Transition to Practice program, which eases the transition from the end of residency to practicing alone.

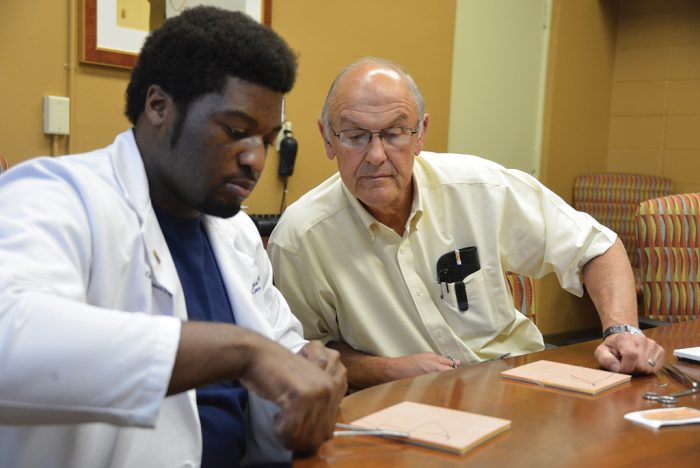

“They come to us after residency and begin working by the side of a practicing surgeon. Then we back off and back off and back off until at the end of the yearlong program, almost every one of them is operating like a junior partner,” he explains. “They also take the first part of their boards the year they’re with us, so liability is not an issue.”

With Nakayama’s help and insistence, the program was eventually certified by, and today operates under, the American College of Surgeons. There are now 45 programs nationwide, including Crisp’s now three-decades-old program. “When I think about the fellowship we created and what we contribute in our own small way, I think to myself, ‘I wish that old rascal [from ACS] was still alive,’” Pannell says.

He also still teaches MCG students – today through the Southwest Campus, where he is clerkship coordinator for surgery, handling the ins and outs of surgery training for students learning in that part of the state and helping recruit faculty to teach them.

“People always ask why they should teach, and I have a [packaged] answer [from] when we were trying to recruit,” he says. “It’s your obligation. Students need to learn one-on-one and that’s the history of allopathic medicine, teaching each other. But more than that, you get refreshed. Seeing a student’s enthusiasm makes you remember why you went to medical school – the ideals you had. They also remind you that you’re not just treating a gallbladder, for instance, that your patients are human beings.”

ABOUT BILL PANNELL

He’s married to Linda, whom he met during medical school – she was in nursing school. She helped set up Crisp Regional Medical Center’s nursing service and helped develop its Wound Care Clinic. For a decade, while he was the only surgeon at Crisp and would work long hours overnight, she would do his morning rounds for him until he got caught up on sleep. They have three children, all of whom played Division I sports in college. He jokes that they got their athleticism from Linda, who was playing semipro basketball when they met. Their children are William, a high school football coach in Roswell; Stephanie, a colorectal surgeon in Ontario, Canada; and Preston, who works in commercial real estate in Atlanta.

ABOUT CORDELE

Nestled between Macon and Albany, Cordele, the county seat of Crisp County, faces many of the problems plaguing other smaller, rural communities – a shortage of physicians. A mix of low socioeconomics and lack of access to health care often leads to complicated health issues for the people who live there. Health problems such as malnutrition and obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, substance abuse and poor maternal and fetal health plague the area.