MCG Student Wins AMA Scholarship

Quante Singleton, a third-year medical student at MCG, says that he always knew he wanted to be a physician, even if he wasn’t sure how he was going to become one.

“I never saw a lot of doctors that looked like me, so I didn’t have exposure to those role models,” says the winner of a 2017 American Medical Association Foundation Minority Scholars Award.

After high school, he joined the Atlanta Fire Rescue Department, where he spent nine years protecting the residents in one of Atlanta’s roughest neighborhoods. A life-changing incident gave him the push he needed to pursue his dream of becoming a physician.

“I got trapped in a burning building, something that the 18-year-old me didn’t really consider could happen when I chose this career,” he says. It made him think about all the things he hadn’t done personally and professionally.

Singleton enrolled at MCG in 2015 and hopes to match with an orthopaedic surgery residency program when he graduates in 2019. It’s a career that piqued his interest after he was treated for a torn anterior cruciate ligament…twice. He says he’d like to eventually practice in Atlanta and “eventually open up some free clinics” in the neighborhood where he worked as a firefighter.

How Sugary Drinks Make Us Fat

Scientists are finding increasing evidence that if we reach too often for a sugary drink, we are setting ourselves up for rapid weight gain.

In fact, scientists have evidence that sugary drinks can quickly make rats – and likely us – resistant to the satiety hormone leptin, even more so than sugar-laden foods.

That means rats don’t get a signal that normally would prompt them to stop eating and/or drinking and they gain weight. The good news is that two days after cutting out consumption of the sugary drinks, rats at least, once again start getting the message leptin is sending.

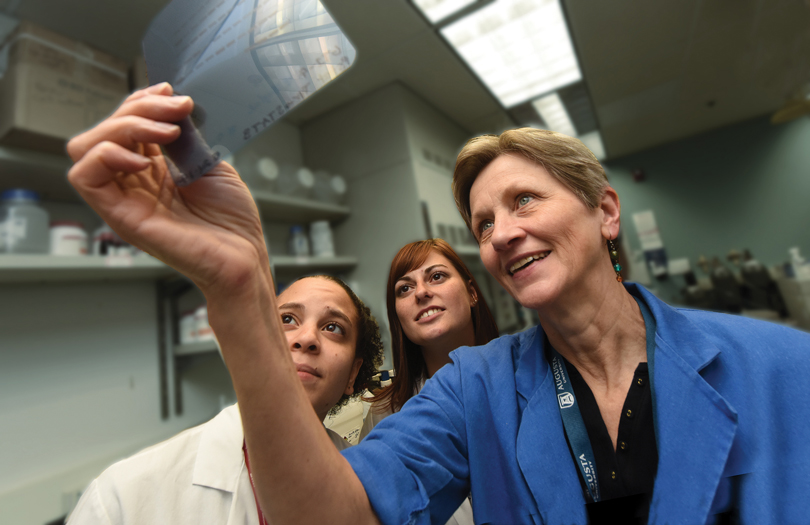

“We think this adds to the evidence that it would be a good thing not to drink a lot of sugar,” Dr. Ruth B.S. Harris, physiologist in the Department of Physiology at the Medical College of Georgia, says of her studies.

About a third of adults and 17 percent of children are obese in the United States and sugary beverages are clearly implicated in this health concern, says Harris.

“When you drink a sweetened drink you’re getting just the sucrose,” she says. “Whereas if you eat foods that are sweet, you are getting the sucrose that is mixed in with other things like protein and fiber.”

That means food must first be digested before glucose reaches the blood while sugary liquids are more rapid fire.

“When you are just drinking sucrose by itself, all you have is the sucrose, which breaks down to glucose and fructose, which get absorbed very quickly, so you see a very quick spike of glucose just because it’s processed in a different way,” says Harris. She recently received a $1.6 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to learn more about the details of what happens when the spikes become too frequent.

The Vitamin Key to Heart Health

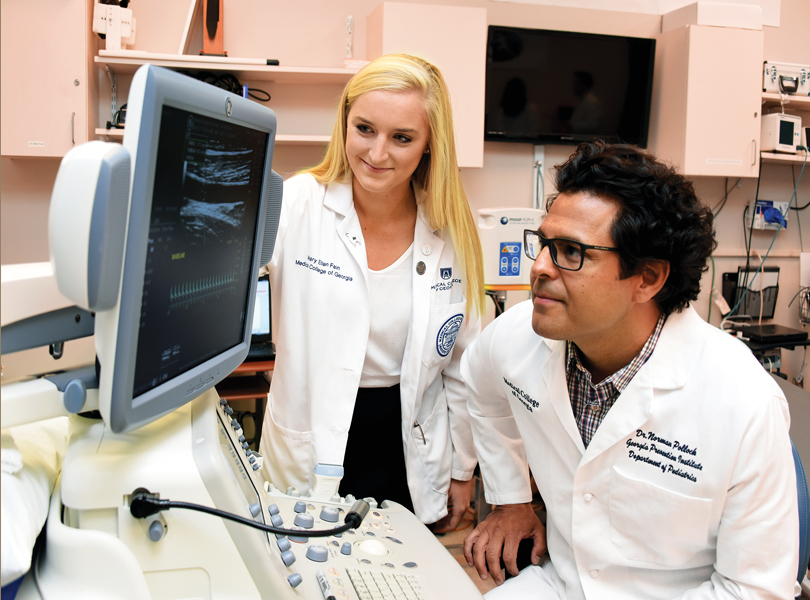

Scientists have found another reason for children to eat their green leafy vegetables.

A study of 766 otherwise healthy adolescents showed that those who consumed the least vitamin K1– found in spinach, cabbage, iceberg lettuce and olive oil – were at 3.3 times greater risk for an unhealthy enlargement of the major pumping chamber of their heart, according to the study published in The Journal of Nutrition. Vitamin K1, or phylloquinone, is the predominant form of vitamin K in the U.S. diet.

“Those who consumed less had more risk,” says Dr. Norman Pollock, bone biologist at the Georgia Prevention Institute at MCG and the study’s corresponding author.

Overall, about 10 percent of the teens had some degree of this left ventricular hypertrophy, Pollock and his colleagues report.

Left ventricular changes are more typically associated with adults whose hearts have been working too hard, too long to get blood out to the body because of sustained, elevated blood pressure. Unlike other muscles, a larger heart can become inefficient and ineffective.

The scientists believe theirs is the first study exploring associations between vitamin K and heart structure and function in young people. While more work is needed, their findings suggest that early interventions to ensure young people are getting adequate vitamin K1 could improve cardiovascular development and reduce future disease risk, they write.

Pollock, who is also leading a novel study of the cardiovascular impact of a vitamin K supplement on obese children already showing signs of diabetes risk, has early evidence that the vitamin levels are lower in obese and overweight children.

New Department To Strengthen State Health Impact

A new Department of Population Health Sciences has been established at the Medical College of Georgia to strengthen the public medical school’s impact on the health of Georgia.

The department initially combines the MCG Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology and the Georgia Prevention Institute, two groups with a common interest in this area and a long history of collaboration.

It will give researchers and educators a more comprehensive perspective on which Georgians are getting sick, what they have and why, and which targeted interventions and treatments are most effective for them, says Dr. Varghese George, chair of biostatistics since 2005 who leads the new department that became effective July 1.

The broadened perspective will translate to expanded research and training opportunities in this developing field that enables better insight into the public health problems of varying groups of Georgians – from stroke to obesity – and how best to address them, says the new chair.

National Cooperative Aims to Reduce Mortality of Rare Leukemia

A national cooperative group trial is making a handful of the country’s experts in a rare leukemia available around the clock, with the goal of cutting by more than half the high mortality rates that occur in the difficult first few weeks of treatment.

Induction mortality for treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia, or APL, can be as high as 30 percent, but for patients who survive those first few weeks, survival rates can soar beyond 90 percent, making it the most- curable leukemia.

“Those rates have not changed in the last two decades despite having blockbuster drugs to treat patients. We want to help, and we want physicians to call us any time if they have an APL patient,” says the National Cancer Institute-supported cooperative’s study chair and principal investigator Dr. Anand P. Jillella. Jillella is chief of the Division of Hematology/Oncology at MCG and associate director of medical oncology services at the Georgia Cancer Center.

Jillella and Dr. Vamsi Kota, an assistant professor in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine and Emory’s Winship Cancer Institute, have developed a checklist they share with those physicians that labels APL a medical emergency and covers early, major concerns with the cancer and its treatment.

Experience with the strategy in about 160 patients in Georgia and South Carolina has decreased induction mortality from an estimated 30 percent to 6.7 percent.

Jillella and Kota estimate about 3,000 APL patients are treated annually by the nation’s 15,000 hematologists/oncologists.

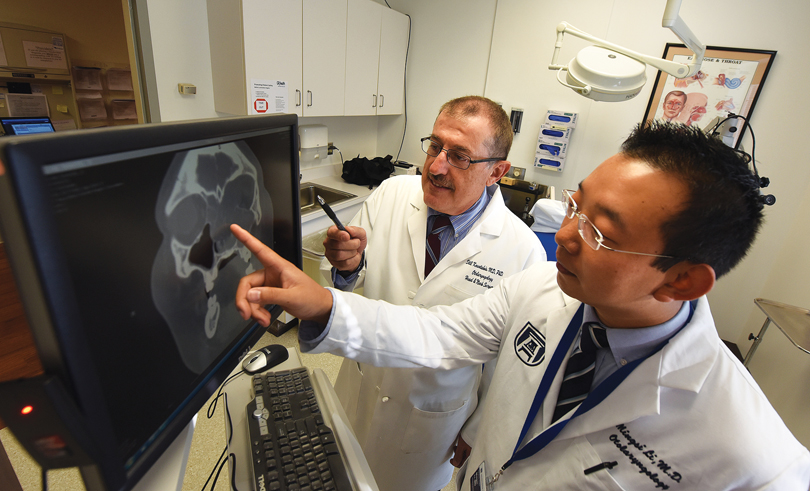

Kountakis Receives Presidential Citation

Dr. Stilianos Kountakis, chair of MCG’s Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, is the recipient of a 2017 Presidential Citation from the American Rhinologic Society.

Kountakis, who also is the Edward S. Porubsky, MD Distinguished Chair in Otolaryngology, was recognized for his longtime service to the society, including serving as its president in 2009-10, and his work starting the group’s journal, International Forum of Allergy & Rhinology, which is now one of the top five otolaryngology journals. He received the society’s Golden Head Mirror Teaching Award in 2015.

In addition to serving as chair, he also directs the AU Health System Georgia Sinus Center and MCG’s rhinology-skull base surgery fellowship program. Kountakis came to the medical school in 2003 from the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, where he was director of the Division of Rhinology and Virginia Sinus Center. He is consistently ranked among America’s Best Doctors.