Dr. Scott Bohlke, ’92 gives new meaning to “home” run

The office doesn’t open for 20 minutes, but there’s already a small crowd waiting outside Bohler Family Practice in Brooklet, Georgia, to see Dr. Scott Bohlke, ‘92.

He is the only physician in this small, rural town outside of Statesboro, Georgia, that spans about three-and-a-half square miles with one flashing stop light and a population of around 1,100.

Bohlke has been the only physician in town for at least 15 years — after the retirement of Dr. Charles Emory Bohler, a 1954 MCG graduate and the practice’s founder and namesake.

“When Dr. Bohler started this practice, he had a starting time (to see patients), and he just stopped when he was finished,” Bohlke says. “He was done when the last patient was done. I kept a similar model. If you sign in between the hours of 8:30 a.m. and noon or 2-5:30 p.m., we’re going to see you. When people here are sick, they don’t have to make an appointment, they know they can just come on in and we’ll see them … and we stay until every patient is seen.”

It’s the type of doctor’s office Bohlke says he always envisioned he’d have, even as a kid growing up in northern Florida.

Bohlke spent his childhood in Jacksonville, Florida, which he jokingly calls the “capital of south Georgia.”

He dreamed of being a physician and fell in love with “small-town medicine” by watching his own family physician, Dr. Carl Drury, ’65. “He was one of my dad’s good friends and saw patients in and around Folkston and Kingsland, Georgia, which is almost right in the middle of nowhere,” he says. “We’d drive the 40 minutes from Jacksonville there to see him and he had an old-school setup. His patients knew him, he knew them, and when you walked the streets and people asked who your doctor was, it was always his name you heard.”

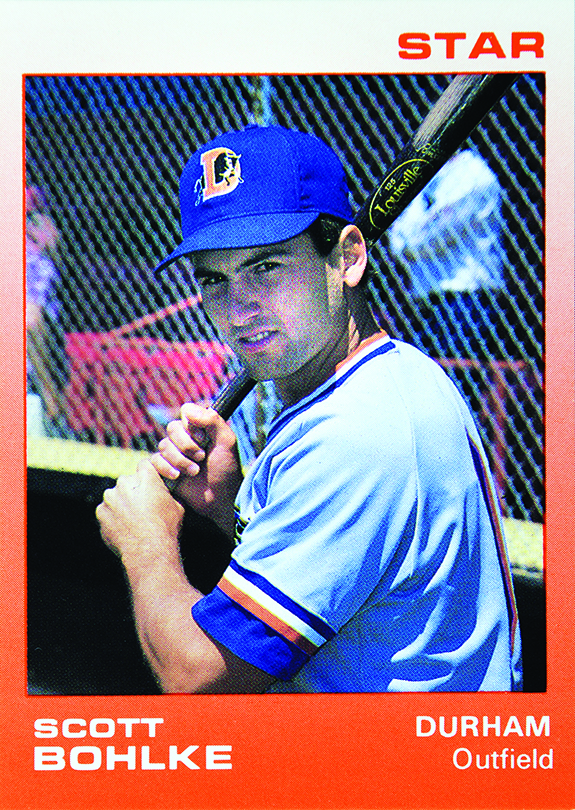

After attending the University of Georgia on a baseball scholarship, Bohlke spent two years playing minor league baseball for the Durham Bulls and Burlington Braves. But the pull of his childhood dream was never far from his mind and he began medical school at MCG in 1988. After completing a family medicine residency at Columbus Medical Center and serving a short time in the United States Air Force, Bohlke began looking for places to begin his own small-town practice.

“I met my wife in Columbus, and we were looking for some place in between (Florida and Columbus),” Bohlke says. “When I met Dr. Bohler, I knew he was a true, old-school family physician. He had been here for around 40 years at that point, so he knew anybody and everybody. I came in the fresh, wet behind the ears, young whippersnapper, so to speak, and I tried to do things one way and was told many times that wasn’t how Dr. Bohler did it.”

Finding his own way took time, he says, but these days it’s his name you hear in Brooklet, and even beyond, when people ask “who’s your doctor?”

“You definitely feel like you’re making a difference for the community and that’s rewarding. You can’t really put a price tag on that,” Bohlke says of serving in such an underserved area of the state, where he knows his many patients by name.

And there are a lot of them.

To keep up with the volume, Bohlke bought the building next door to his practice on the Brooklet town square a decade ago and hired two nurse practitioners — one of them Dr. Bohler’s daughter, Rene B. Childree — who see patients by appointment. He also sees patients there one day a week and still carries a full caseload of patients at the walk-in clinic.

It’s a model that can be taxing on family and personal time, and his long hours are likely why none of his four children even considered a career in medicine, he says. While he still calls his work fun, he also admits it can be frustrating – not because of what he can do, but because of what he can’t do.

Because Bulloch County, which includes Brooklet and nearby Statesboro and Portal, is largely rural and many of his patients are self-employed, lack insurance or even simple transportation, the problems they come in with are bigger and badder.

“They tend to forgo a lot of the preventive stuff, which I feel like is the biggest problem, especially in primary care,” he says. “For instance, if a lot of these people had gotten their colonoscopy at age 50, they wouldn’t have the cancer they have now. But they didn’t because they didn’t have the insurance or they just couldn’t afford it.”

Bohlke knows those problems are not limited to Brooklet. As a board member of the Georgia Board for Physician Workforce, which works to identify and meet the physician workforce needs of the state, he has a birds-eye view of the problems that face this largely rural state.

They are problems like the eight counties in Georgia with no physician – not one. Eleven counties have no family medicine physician. The numbers look even worse when you count the number that don’t have internists — 37, pediatricians — 63, obstetrician/gynecologists — 75, and general surgeons — 78.

Eighty-nine, more than half of the state’s 159 counties are designated by the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration as a Primary Care Health Professional Shortage Area, calculated by looking at an area’s population to provider ratio, the percentage of people living below 100% of the Federal Poverty Level, infant mortality rates and the travel time to the nearest source of health care. That means the people living in these areas don’t have adequate access to health care, and when they do access the system, they often show up acutely ill and in need of more complex medical care – like the people who show up at Bohler Family Practice with late-stage colon cancer.

Bohlke and his 13 fellow Georgia Board members are up for “trying anything and everything” to get physicians to underserved areas, he says.

For instance, the board offers a student loan repayment program to incentivize physicians to practice in those places. The state will repay $25,000 per year for up to four years to physicians who practice in medically underserved and rural areas of Georgia — defined as places with a population of less than 50,000.

“To some degree, part of the problem is the debt students carry, which precludes physicians from going into primary care because of the pay differential between what other specialists make and what primary care physicians make,” he says.

Adding another layer to an already complex issue, enticing people to open solo practices in small towns is more difficult because of what should be simple government and insurance paperwork.

“Reimbursement is already difficult. As a single individual trying to negotiate with a large insurance company, who’s going to win,” Bohlke asks exasperatedly.

But loan repayment, he says, won’t be enough to keep physicians in underserved areas long term. He reasons that on a federal level, doctors in urban areas like Atlanta are reimbursed at a higher rate for care of Medicare patients than those in rural and underserved areas – what he calls the ROG, or Rest of Georgia. “The thought process behind that was that the cost of living in those areas was higher,” Bohlke says.

Still, there are high but different costs to practicing in rural Georgia. “We need to find some way to incentivize the folks that have been out here in the trenches. If we could get less government regulation and fewer hoops to jump through, there would be a lot less frustration with the process. You always want to try and help more and more patients, but it gets more and more difficult.”

While the bottom line is better patient care, having more physicians in underserved areas is also healthy for Georgia’s rural economies. According to estimates by Tripp Umbach, a firm that specializes in community health research, strategic planning, economic analysis, feasibility studies and market research: Each physician who establishes a primary care practice in an underserved area generates $3.6 million in health care utilization savings; an average of $2.2 million in economic impact; and creates an average of 14 additional jobs.

“Look around my town, we have two pharmacies, we have a medical supply store across the street,” Bohlke says. “Those things would not be there without a medical practice here — they wouldn’t be viable. Not only is it about the patients you care for, these practices are a great driver of the economy.”

One of the patients waiting to see Dr. Bohlke during afternoon clinic hours is Hershel Beacham. He and his wife, Debra, have driven from Statesboro, a larger, but still medically underserved community, to see him – the same way they’ve done since Dr. Bohler was in practice. “I’ve been seeing (Dr. Bohlke) for decades. We come here because we love him,” Hershel says.

Hershel, Bohlke suspects, is bleeding internally, but it’s still a mystery where. He’s been to a gastroenterologist in Statesboro for an upper and lower gastrointestinal study, but the results were normal. The same physician ordered a capsule study, which uses a wireless camera for a closer look at possible gastrointestinal bleeding. In the meantime, Hershel only weakened – his iron and hemoglobin levels continued to drop. His GI doctor ordered more labs but offered no answers, much to Hershel and Debra’s dismay.

“He ended up having to have a blood transfusion on Feb. 13, his iron and hemoglobin levels were so low. It scared us to death,” Debra explains. “Dr. Bohlke, will you please help us?”

With a reassuring look and hand to Hershel’s back, he assures them he will. “I’ve got homework,” he tells them. “We need to look into this further. I’m going to look up his test results and blood transfusion records from the hospital. We’ll figure out a game plan and go from there.”

“That’s fine! We trust you,” Debra says. “Well, that’s your problem,” Bohlke tells them laughing.

“I’ve asked this man 50 times why he stays here…,” Hershel says.

“The reason I came here was because of the need,” Bohlke says. “Do we need another doctor in the greater Atlanta area? Or do we need them here?”