Nelson is a 56-year-old man who came to the hospital for a PICC line but developed a heart rhythm issue that you have been called in to address. Staff has hooked him up to the biphasic defibrillator, and the team has airway equipment ready just in case.

“He has a pulse,” you’re told. “What should we do?”

You look around at the team gathered around the patient’s bed. Jose is handling airway management. Phyllis is working the defibrillator. Andre and Maria are doing chest compressions, and Erin will administer medication.

Five very capable people, all looking to you for guidance.

“He’s still bradycardic and hypotensive,” someone says. “Please let us know what this rhythm is before we proceed.”

This is the moment you’ve prepared for — that point where the classroom comes to life. But now that it’s actually happening — and in real time — it’s just so much. It feels like a play where you’ve practiced your lines but never actually rehearsed, at least not with a full cast, and now you’re suddenly on stage for a performance. And it’s more improv than you expected. And quicker, too. So much quicker than you’re ready for.

“There’s not a QRS after every peak,” you’re told now. “Even if you’re not certain, please let us know what you think it is so we’re all on the same page.”

That prompt — that sounded like a scolding. Like they know you’re floundering. Because the team shouldn’t be telling you what you need to do. You’re the doctor, right? You shouldn’t need prompting.

“It’s a Type-2 — also called Mobitz — second-degree AV block,” someone’s telling you now. “This one is dangerous. The wave form just changed and he’s more hypotensive. Normal saline and O2 are going. What should we do?”

So much is churning around in your head, but all of it is drowned out by that one question:

What should we do? What should we do?

Though the above scenario technically took place at Augusta University Medical Center, it was in a little room off a hallway in the anesthesia department that looked more like a storage room than a treatment room. And the team waiting for direction — Jose and Phyllis and Andre and Maria and Erin — never existed. Nor, thankfully, did the patient.

Instead, it was all part of a sophisticated virtual reality simulation designed to train medical students, one made possible in part by a small experiential learning grant and the assistance of the Center for Instructional Innovation.

Expanding the Classroom

A self-described simulationist, Dr. Vikas Kumar, associate professor of anesthesiology and perioperative medicine at the Medical College of Georgia, is the simulation director for the anesthesiology department and is eager to add virtual reality to traditional education. He doesn’t, however, want to replace the simulation assets already being used; he just wants to augment them with virtual reality.

Traditional simulation, he says, is resource-intensive as well as costly. Not only does it require manikins, which can cost up to $80,000 apiece and require an expensive maintenance contract, but the scenarios also necessitate planning, actors and a physical location to host the activities.

“With virtual reality, we can go to the learner,” Kumar says. “Or I can just ask them to come to our virtual reality room.”

Right now, the virtual reality room is that cluttered little space in the hospital, but with the help of a ridiculously powerful laptop and a headset, that little room can become a realistic three-dimensional treatment room complete with a sick patient, an interactive medical team and the goal of providing an immersive, highly realistic learning experience in a no-risk environment.

“We used to have this policy of ‘learn one, see one and do one,’” Kumar says. “I can learn by watching videos; I can see maybe one or two crisis scenarios in a year; but it would be hard to do one in a real-life scenario. But those things are changing, and that’s where simulation and virtual reality make more sense.”

And here is where that team of visionary thinkers from the Center for Instructional Innovation comes into play, because that team is giving Kumar the support to make it happen.

‘Cheers’ Had it Right

For someone who considers himself to be, at his core, a school teacher, Dr. Zach Kelehear might seem like an unlikely facilitator for such a detailed and technical medical scenario, but as vice provost for instruction, that’s exactly what he’s supposed to be doing.

In that role, Kelehear oversees the Division of Instruction and Innovation, which includes 13 units essentially wrapped around three basic areas: instructional innovation; student success; and high-impact practice, a term that includes things like study abroad, the Center for Undergraduate Research and Scholarship (CURS), the Honors Program and Career Services.

In other words, he’s with students from orientation to the point where career services helps them plan for life after college. And in the case of medical education, that interaction extends farther.

In a sense, those basic areas — instructional innovation, student success and high-impact practice — are a three-legged stool built from 2016’s Quality Enhancement Plan (QEP), a proposal to enhance student learning required for accreditation by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC). Called “Learning by Doing,” the plan is defined by several specific elements but is, broadly speaking, a commitment to an expanded view of instruction and opportunity.

In basic terms, it’s experiential learning — literally learning by doing — and everything encompassed by that idea.

By making the educational experience more dynamic and engaging, Kelehear hopes to involve students in ways that reach beyond the stereotypical classroom lecture.

“We know that when students feel invisible, they become disconnected” he says, which is why he is so invested in creating and enhancing opportunities for students to connect — with other students, with faculty and with engagement opportunities.

“I think Cheers had it right,” he says. “It’s all about connections and finding a place where you belong. It’s not a lonely journey here at Augusta University — it’s a community journey where students will be surrounded by shared interests, by peers, by faculty and by learning spaces where people know your name and care about you.”

That desire to be where, like the TV theme song suggests, everybody knows your name doesn’t end with students, however. The need to feel assisted and supported is important to faculty as well, and this approach, with the help of the Center for Instructional Innovation, supplies faculty members with strategies to innovate their approaches as well as the tools to implement new types of content.

“Student success is the first measure of a successful mission,” Kelehear says. “Success in which faculty feel like they’re supported in their own journeys — that’s a fast second.”

And Kelehear has a hand-picked team of innovators helping faculty develop those exciting new strategies that help them do what they do best — engage students in meaningful and interesting ways.

A Dream Team

“The first couple of weeks I was here, Dr. Kelehear said, ‘What would you think if I told you we’re going to add to the team some individuals with diverse talents and creative skill sets,” says Stacy Kluge, an instructional designer at the Center for Instructional Innovation. “My jaw dropped. I was literally flabbergasted.”

Kluge, who had just arrived in the Center for Instructional Innovation after 11 years at Georgia Southern University’s teaching and learning center, had interacted with colleagues from enough other institutions to know just how rare this vision was.

“The teaching and learning centers in the University System of Georgia have very good people, experts in faculty development around teaching and learning, but they don’t have people with specialized skill sets like videography or medical illustration or graphic design,” she says. “New configurations of people allow for new configurations of work. There is no telling where this is going to go.”

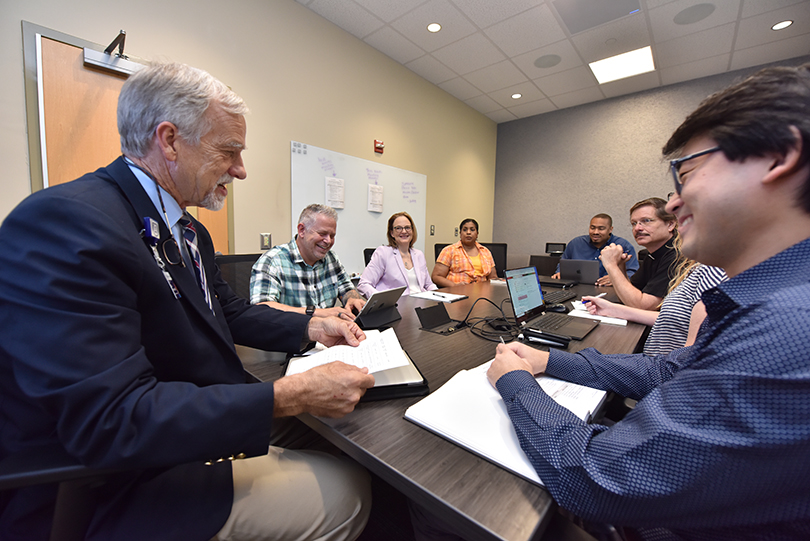

Located on the second floor of University Hall on the Summerville campus, Kelehear’s team is made up of just those types of people: instructional designers, videographers, graphic designers, medical illustrators and problem solvers who have the skills to design, create and implement just about any instructional idea. However, Kluge says, perhaps even more impressive than the skills they bring is the diversity of thought they provide. Every project they consider gets at least one meeting where everyone on the team is there to give input.

“At other places, a consultation will typically be one-on-one,” Kluge says. “A faculty member will come in and need help with something, and there’s not really space for everyone on the team to discuss it and throw out possibilities.”

Not so here.

“We have the ability to come up with creative problem-solving solutions in a way that we’ve not been able to offer before in the university setting,” says Lynsey Ekema, a board certified medical illustrator. “We all have these backgrounds that are so unique, and we bring perspectives from every different avenue.”

Though they have lots of technical abilities and can easily and effectively turn technology loose on just about any problem, she says they also understand that not every problem is best solved by technology.

“I think at the core, everything we do is basic instructional design,” Kluge says. “It’s helping faculty members clearly define what it is they’re trying to accomplish, how best to assess it, what kinds of activities students need to do to get there and what kind of technologies best support the whole process.”

While every member of the team sees value in the proper use of technology, it’s important to all of them that technology never becomes a stumbling block for innovation.

“Education and instruction, especially at the university level, happens en masse, but learning is always an individual activity,” says Jenn Rose, an instructional designer. “Trying to deliver instruction to this very different audience of learners in the current environment can be overwhelming and very challenging, and I think a big part of why we’re here and where we benefit the student experience is that we can bridge that gap for professors.”

In Kumar’s case, that meant finding a way to implement innovation for medical education, something that started with an Education Innovation Fund (EIF) grant.

Funding the Bridge

“One day I was going through my email and saw this email about the EIF grant,” Kumar says. “I didn’t have much hope, to be honest, but I submitted the application, and when it was accepted, it was a major boost for me.”

The grant, with a maximum award of $2,000 per course or experience, is meant to encourage experiential opportunities for students and faculty. For Kumar, that money helped purchase the headsets. Others have used the funds to incorporate gaming as a form of immersive learning. Another project is using student researchers to synthesize a drug for a neglected disease. All are providing experiential learning.

But besides the economic support, the ongoing professional support has proved beneficial.

“They have people with skills to develop virtual reality scenarios; they have a videographer and a video editor to make everything look good,” Kumar says. “They are a good resource, and we try to meet with them on a regular basis.”

This is important, he says, because education is not a static field.

“Today’s learner is different than learners from the past,” Kumar says. “If you ask them to sit in a classroom and listen to a lecture for 45 minutes, I think they would probably pay attention for 15 minutes to a half-hour. So immersive learning has shown to be very effective for teaching, and that’s why simulation is growing, and virtual reality adds an extra layer of immersion.”

Currently, Kumar is researching the effectiveness of the virtual reality simulations on a small scale with the hope of proving their worth and then expanding.

“We’ve got about 15 medical students who were trained on the virtual reality cardiac support scenario, and everybody said this is better than the way they were taught before,” he says. “That’s positive feedback, but that’s not the main goal. The main goal is to see if they are utilizing their skills and knowledge with virtual reality in the real world.”

Kumar is excited by the opportunities provided by the Office of Instructional Innovation and the EIF grant and says he’s eager to continue the relationship and explore other ways they might improve student learning.