Innovative New Center Features Labs Without Walls

Picture a scientist, and you’re likely to envision a solitary figure wearing a lab coat toiling away behind a closed door in a room filled with vials and test tubes.

Now, reimagine the scene: That solitary figure actually has several colleagues close by, and the door is generally open as they move seamlessly into nearby labs to confer with researchers studying related or complementary projects. Or the scientists are out of the building altogether, perhaps at a conference in Paris or meeting with a research collaborator in New York.

The lab of today, practically speaking, has no walls. Biomedical science has grown too large, complex, collaborative, multidisciplinary and fast-paced to accommodate careers spent in isolation behind closed doors.

“The landscape of biomedical research has changed,” says Dr. Babak Baban, DCG interim associate dean for research. “The traditional approach — one PI (principal investigator) doing one line of research in their own lab — that’s no longer efficient.”

Baban, who earned his Ph.D. in immunology from the University of London, embodies the spirit of collaboration. Necessity required that he become a quick study of his environment, and incessant curiosity prompted him to tap into the expertise of others and form lasting bonds. He brought that mindset to Augusta when he joined the AU faculty, pursuing multiple projects with colleagues both on and off campus. When he was named to his DCG position last year, one of his highest priorities was helping to cultivate this spirit of collaboration between the DCG and Augusta University campus.

His goal was quickly made tangible, with Dean Carol A. Lefebvre heartily endorsing his proposal to create a center devoted to this purpose.

Editor’s note: As this edition of the magazine was going to press, the importance of the DCG’s research initiative was being highlighted as never before. In addition to campus-wide efforts to conduct mass COVID-19 testing, treat patients with the virus and offer extensive education to the public about related topics such as social distancing, biomedical researchers were hard at work contributing to nationwide and worldwide efforts to develop treatments and a vaccine. Dr. Babak Baban, who holds a joint appointment in the Medical College of Georgia, quickly embarked on a pilot study with his colleagues . On an incredibly compressed time schedule, the researchers – Baban along with Drs. Krishnan Dhadapani and Kumar Vaibhav in the Department of Neurosurgery, MCG Dean David Hess, postdoctoral fellow Dr. Evila Salles and Ph.D. student Dr. Hesam Khodadadi – were able to simulate COVID-19 in a mouse model, a breakthrough unleashing extensive potential to test new therapies. We will keep readers apprised as their progress unfolds.

The result? The DCG Center for Excellence in Research, Scholarship and Innovation (CERSI), which launched in January.

“I started working on it right away,” says Baban. “While the basic value of biomedical research hasn’t changed — it is indispensable and very precious to the medical field — the pace has become much more rapid, and science is becoming borderless. With these changes, no individual lab can possibly have enough resources in terms of expertise, facilities and equipment to reach its potential. This is the main drive of the center.”

The center serves as ground zero for DCG faculty, residents and others involved in research, ensuring they have the resources, information and connections necessary to expedite their studies and expand their scope. “The center will have two wings: basic biomedical and clinical,” Baban says, citing the DCG’s mission since its inception 51 years ago of excelling in both basic research — studying cells under a microscope, for instance — and clinical research — translating lab results to patients, all for the ultimate benefit of better health.

Both wings will have a director and project director. Also, Lefebvre will appoint a board of directors, and its members will create internal and external advisory boards.

Says Lefebvre, “We will have extensive input and ongoing dialogue with a host of partners helping us achieve our highest aspirations for research and optimal oral health. Dr. Baban has done an extraordinary job putting this priority on a fast track, and we anticipate remarkable and far-reaching progress.”

For instance, Baban envisions linking researchers studying a particular protein with colleagues down the hall studying a related protein, then expanding to scientists in entirely different disciplines, campus-wide and beyond, probing the systemic implications of conditions such as periodontitis, oral cancer and temporomandibular joint disorders.

“We want to make our science more visible while increasing productivity,” Baban explains. “We have adopted a new model of interdisciplinary research, rearranging existing resources and putting them together like a core facility. We are categorizing our projects so we can present them in a way that ensures everyone can build on each other’s progress.”

This involves not only sharing resources, but continually creating new ones as opportunities present themselves.

“We are making the most of additional resources at this point,” Baban says, “but as we grow, we plan to bring in new funding. For example, we anticipate adding personnel and a unit for community engagement, which can attract parties that can help us conceptually or financially. We have a very good feeling that resources will flow into the center.”

The center’s strongest assets, he says, are already firmly entrenched. “We have an excellent faculty and an excellent reputation,” Baban says. “This is the heart and the core of the facility.”

And the center will only enhance these priceless assets, he says, noting its ability to recruit and retain researchers. Those researchers will then form new scientific avenues that will attract new funding, a process that will continually replicate itself.

“You have to look at the context of the times: priorities, resources and research environment,” says Baban. “Everything really came together at the right time. We saw the opportunity and necessity and applied it.”

Faculty enthusiasm is high, Baban says. “Everybody, including the dean and provost, have been so supportive. Everybody is ready to contribute.”

Mastering Challenges

Dr. Mohamed Meghil had two steep hills to climb recently.

First, he had to compete against stellar competition in an Augusta University research competition.

Next, he had to concisely and persuasively communicate the importance of his research to an illustrious panel of judges.

The first part, he felt, was more than doable. Having spent several years helping elucidate the role of a specific bacterium in periodontitis, he knew his research was vital. Fully half of adult Americans have periodontal disease, a gum disorder that can lead to tooth loss and systemic health problems. He and his colleagues are excited about the potential of the novel inflammatory pathway they have identified in treating the disease.

The second part should have been tougher. Augusta University sponsors an annual Three-Minute Thesis competition, inviting graduate students to present their findings in laymen’s terms in approximately the amount of time it takes to reheat leftovers in a microwave. This is where Meghil might have floundered; Meghil and his wife,

Dr. Linah Shahoumi, mastered the English language only after moving from their native Libya to Pittsburgh in 2011, eager to further their studies in oral biology. They enrolled at Augusta University a year later, earning master’s degrees in the field in 2014. They then completed a Ph.D. in oral biology and maxillofacial pathology. Meghil is currently completing a periodontics residency at the DCG.

It comes naturally to him to drill down on the complex physiological processes taking place in oral disease; “I love doing research,” he says simply. But it’s tough even for those who have spoken English fluently all their lives to make complex biomedical research understandable. Could Meghil manage this feat based on a mere seven-year immersion in the language?

The answer, he learned last spring, was a resounding “yes.” Meghil won the 2019 Three-Minute Thesis competition. He has won national research competitions as well, awards he is most excited about because of their potential to raise awareness of the importance of good oral health.

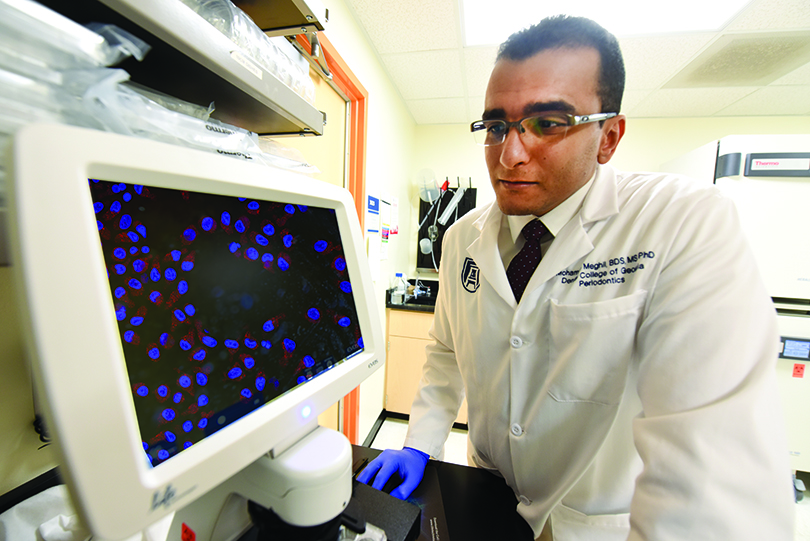

He and his colleagues are specifically studying a bacterium in the oral cavity called Porphyromonas gingivalis. “It seems to hijack the immune system and keep dendritic cells from functioning and awakening the immune system,” he says. “I call dendritic cells the quarterbacks, because they set a plan of defense in action. But the bacteria render them hosts of infection.”

Meghil notes that “In the case of periodontitis, the bacteria hide inside dendritic cells and are allowed to proliferate unchecked. This is a major factor in severe gum disease, and something is absolutely going on at the genetic level. That’s what we’re currently studying.”

Periodontitis, characterized by inflamed and bleeding gums, currently has no cure; the 50 percent of Americans with the condition can stay on top of their symptoms with professional cleanings every three months and surgery if needed to clean the bone beneath the tissue, bone that will inevitably disintegrate if left untreated, Meghil says.

“Success of saving teeth depends on how much bone the patient has already lost when treatment begins, and it can be a considerable amount, considering that this is initially a silent and painless disease,” he says.

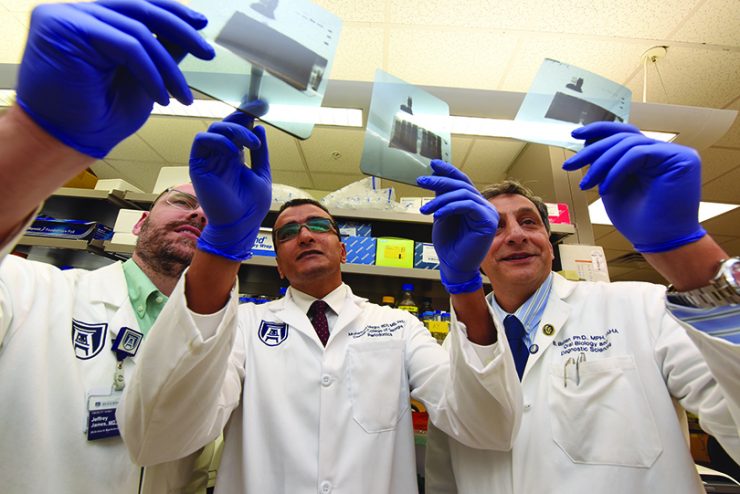

He and Dr. Christopher Cutler, chairman of the DCG Department of Periodontics, are isolating the dendritic cells in tissue samples to further understand how Porphyromonas gingivalis bacteria trick dendritic cells into malfunctioning. “This bacterium has extensions from the surface called fimbria, and the short fimbria appear to be implicated,” Meghil says. “We are hoping that by manipulating the fimbria, for instance by adding or deleting different proteins, we can halt the disease process.”

He is thrilled to be pursuing his research at DCG, which he cites as one of the most progressive dental schools in the nation, and he looks forward to continuing his work both in the lab and the classroom as his career progresses. “Interacting with students makes me happy,” he says. “I’m grateful to be in an environment where I can do all the things I enjoy.”