In 1934, a faculty member and chair in the Medical College of Georgia’s then Department of Anatomy was tapped as dean during a time of turmoil. But Dr. George Lombard Kelly, ’24, was used to rising to the occasion.

Department of Anatomy was tapped as dean during a time of turmoil. But Dr. George Lombard Kelly, ’24, was used to rising to the occasion.

The year before, the University System of Georgia Board of Regents had decided to close MCG. The Great Depression had just ended, and the Regents cited several issues, including lack of funds, equipment and enough full-time faculty. At that time, MCG already was part of the University of Georgia, having been annexed as one of the impacts of the Flexner Report of 1910, which transformed medical education by establishing major criteria to judge the quality of education offered. But citizens, alumni, students and faculty, including Kelly, rallied and the regents reversed their decision.

Later, as dean, Kelly hustled to make changes and help reinstate the school after it lost its “A” rating by the Council on Medical Education and Hospitals and was dropped as a member of the Association of American Medical Colleges.

He helped save MCG not just once, but twice. The man who would become the school’s first president after MCG separated from the University of Georgia in 1950 is still remembered today through the administration building on the university’s campus that bears his name.

But that is only one side of the man, who’s also been described as someone who never gave up, who loved and supported his students and his family, who was far ahead of his time in his thinking about inclusion and had great foresight regarding medical education. And it’s also why an endowment was recently established by an MCG faculty member, to support a named lectureship and seminar room in Kelly’s honor.

The story

When Dr. Sylvia Smith became chair of MCG’s Department of Cellular Biology and Anatomy in 2013, she says that like many, she knew of Kelly from that administration building and his portrait displayed in the MCG Dean’s Suite. “But I didn’t understand who he was.”

As chair, she started reading about the history of the department and didn’t realize, as others might also not be aware, that Kelly joined MCG — following graduation, internship and a year of research at Cornell Medical School — as an associate professor in its Department of Anatomy, and later professor and chair.

She picked up a copy of All I Did Was Plan Ahead, a biography of Kelly written by Jane Downing Chandler, wife of his former student, the late Dr. A. Bleakley Chandler, ’48. She read how the Augusta native had been admitted to Johns Hopkins Medical School, then later, MCG, having to withdraw from both medical schools due to illness. Other men might have been beaten down and chosen to pursue another field, says Smith — and indeed, Kelly taught Latin and science and worked as a newspaper reporter for a time. His world tipped upside down again when Adeline, his young wife of five years, died of tuberculosis.

No one knows quite why, but after his wife’s death, Kelly reached back out to then-dean of MCG, Dr. William H. Doughty Jr., to ask if he should try medical school a third time. It’s reported that Doughty made the telling statement that if Kelly were able to finish, he would someday take his job as dean of the medical school.

Those words seemed to galvanize Kelly. From being a medical school dropout, he studied and worked in the Department of Anatomy over the next six years, graduating from MCG in 1924. Smith also points out other interesting anecdotes: During postgraduate research at Cornell, Kelly worked with Dr. George Papanicolaou, developer of the Pap smear; it’s been reported that Kelly likely introduced Papanicolaou to MCG pathologist Dr. Edgar Pund, whose work in early detection of cervical cancer led to use of the Pap smear being widely accepted. Kelly is also credited for starting an early journal club, the Dugas Club, named for an MCG founder and serving as a forum for faculty student discussions of medical research and to retain and attract outstanding faculty.

“This is an amazing person,” says Smith. “Here’s somebody who’s a leader. You can tell it from reading about him. People recognized his leadership … [And] what I loved reading about it was, here’s somebody who was our faculty member first. … He was one of us.”

Smith herself joined the faculty at MCG in 1991. Around five years ago, she says, she began to feel it was time to give back. “I was glad to have been a faculty member here, glad to be part of MCG. I think you get that feeling of ‘what can I do?’” she says. She decided she wanted to establish an endowment, “but I wanted it to be in Dr. Kelly’s name.”

She didn’t want to honor the president or the dean, but the man she’d come

to know through her research: The one who loved to dance and might be seen with students at a fraternity party on a Saturday night; who was a demanding teacher but a fair one, and inclusive far ahead of his time, supporting both female and diverse medical school candidates and faculty; who loved anatomy and continued to use that knowledge in writing clinical works on women’s health; who recognized the importance of collaboration and worked to promote interaction and scholarly discussion among faculty and students. “He was definitely a century ahead of his time to realize that those communications, those discussions about scholarly work and scientific work were so critical,” Smith says.

The G. Lombard Kelly Lecture was formally endowed in 2020 by Smith and her husband, Kenneth, to continue Kelly’s legacy, his belief in research and to inspire current and future students and faculty with his vision, determination, commitment and perseverance. “What I like about this is that this is a living legacy,” she says. “Every year, Dr. Kelly’s name comes up again as we talk about the lectureship.”

The Cellular Biology and Anatomy Seminar Room was also named after Kelly. “When you do major things like he did, the things that led up to it — he was a leader of the department, a faculty member — that was the scaffold upon which all those other accomplishments were built,” she says.

At home

The man who was a dean, a president, a professor and an anatomist had another title as well: For his family, he was known more simply as PawPaw.

While Kelly was still completing his medical degree, he met and married a young widow, Ina Melle Todd Hoffman, who was working in the dispensary at the university’s Newton Building. He adopted Ina Melle’s daughter, Margaret, then 3, and the couple would go on to have two other children, Georgia Anne and George Lockwood. According to Anne’s daughter Kathleen Sullivan Elms, Georgia — called Anne — was named for Kelly since he didn’t know if he would ever have a son.

Kelly was a loving father and, later, grandfather, doting on young Margaret and later in life, working alongside daughter Anne in the publishing company he owned, Southern Medical Supply Company. A letter to son George written in 1960 counseling him on treatment of his granddaughter Ingrid’s hemangioma (a bright red birthmark made up of extra blood vessels in the skin) ends with this postscript: “I am most grateful to you for having always been such a fine son, of whom I could always be extremely proud.”

His grandchildren and great-nephew remember him as being a quiet man but loving in his way. After all, although Kelly was known as a supportive teacher, he was also nicknamed Stoneface, and it was said that he could be silent in seven languages. “He was very studious, and I remember him as being very thoughtful in terms of whenever he spoke. It was obvious he wasn’t speaking off the cuff,” says his grandson Nathan DeVaughn, Margaret’s son. “It was something that had been considered.”

By then in his 60s and 70s, Kelly and Ina Melle would have the family gather at their home at the corner of Milledge Road and Gardner Street every Sunday for dinner after church. Kelly had a routine: After church, he’d retire to his study, until Ina Melle stepped on a buzzer in the floor of the dining room to let him know dinner was ready. Following the meal, which always ended for Kelly with a cup of coffee topped with a scoop of vanilla ice cream, he’d settle in the living room to read the Sunday paper, speaking with the grandchildren as they played with toys nearby.

That he was an important man was something the grandchildren all knew and accepted —“We’re very, very, very proud [of him] … but it’s a quiet proud. … Nobody made a big deal out of it,” says Elms. “PawPaw was always very humble. And he didn’t expect to have any recognition.”

The rich details of Kelly’s work would come later to that generation. Hunter Baggs Jr., whose grandmother was Ina Melle’s sister and who is only six years younger than Kelly’s son George, was like another son. He says that as with others in the family, he learned about Kelly’s impact on MCG and the greater Augusta community when he was around collegeage and older. “I realized what he had done more than I had ever known before,” he said. “He was very inventive and open to new things and didn’t want to just let things go along. He wanted to plan ahead and think of the future. That’s the kind of person he was.”

Strong ties

When Elms learned that Smith planned to honor Kelly, “It became even more special when it was somebody presently there who never knew him … and just somehow just started researching him and found him worthy of it. … I think it’s really pretty amazing the more you delve into it and the more you look into it and the more you hear about all the things he had to overcome. … My family’s always been very strong and very passionate about things, and I think we must have gotten that from him in many ways.”

Indeed, the family’s ties to MCG through Kelly have remained as strong during the decades since his retirement and even today. In 1965, Baggs joined MCG to establish the hospital’s first patient accounting and collections department. Elms completed a nursing degree at Augusta College and further professional training at MCG’s then-School of Nursing and worked in its hospital during the ‘80s. In the ‘90s, DeVaughn conducted brain research with former MCG neurologist and neuropathologist Dr. Manuel Casanova, then moved into the school’s IT department. His wife, Linda, was MCG’s director of admissions at that time, where she remembers imparting Kelly’s legacy and impact to incoming students. And Carl Kelly Zainaldin, a great-grandson, is a 2020 MCG graduate who attended MCG’s second four-year campus in Athens, the AU/UGA Medical Partnership; he is now a second-year resident in internal medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Then, during the formal dedication for the G. Lombard Kelly Lectureship and Seminar Room, AU President Dr. Brooks Keel shared his connection with the Kelly family: His mother, Mildred, worked with Kelly’s son-inlaw, surgical oncologist Dr. Daniel B. Sullivan, ’49, as a medical assistant for 30 and a half years. It was a happy reunion when Keel met once again with Kelly’s granddaughters Kathleen Sullivan Elms and Pat Sullivan Briscoe at the reception. “I never had the honor of meeting Dr. Kelly … but I have very fond memories of your dad and your mom and how much they meant to my family, to me and my mother especially,” he said. “To be able to be here and to honor now your grandfather is very special to me.”

The G. Lombard Kelly Administration Building, where Keel’s office is located, sits just across the street from the newly named seminar room, a testament to both sides of the man who persevered through the worst of times, enjoyed the best and always looked ahead to the future. “I am very grateful he’s being honored for his teaching,” says granddaughter Ingrid Kelly, George’s daughter. “I thought that was really touching. … He loved what he taught, and he also had great compassion for the students, so to honor that … He loved more than just the medicine. So, I think when she is honoring him, she is honoring the teaching profession and she’s honoring that relationship between student and teacher, and that’s where it all begins.”

Stories to remember

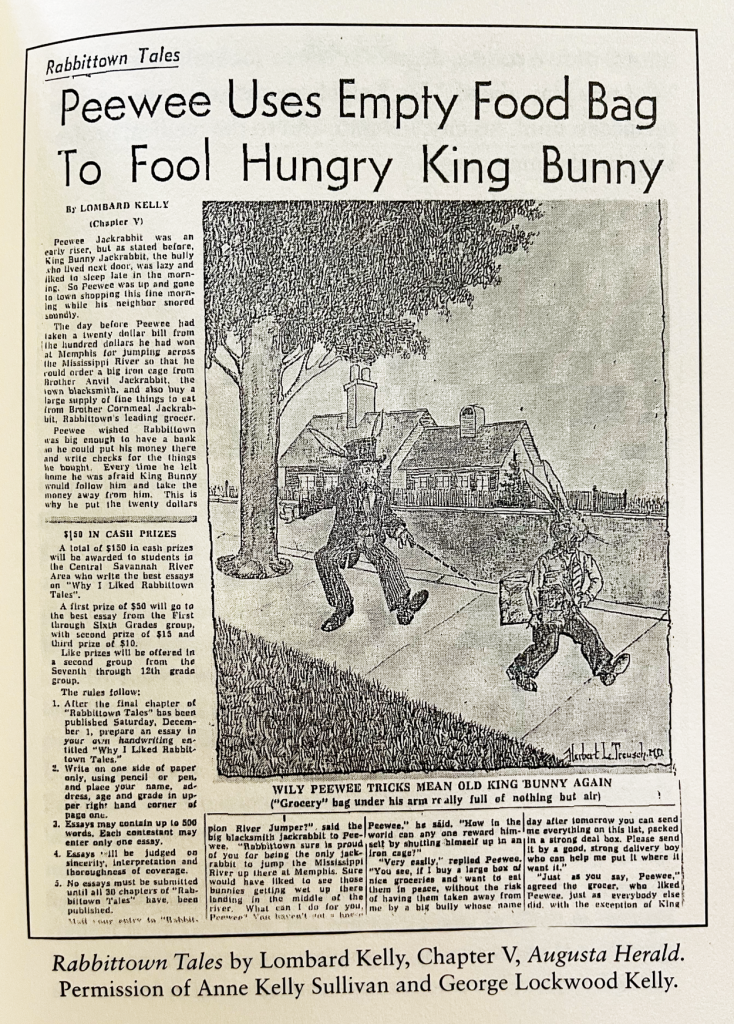

“Rabbittown Tales” was a series of 30 stories published in the Augusta Herald newspaper by Dr. G. Lombard Kelly and were just some of the hundreds of stories he dreamed up to entertain his children.

The protagonist, a jackrabbit named PeeWee, often got the best against King Bunny, a lazy dandy who slept in, made noise and liked to cheat. Kelly’s family says that PeeWee was likely modeled after Kelly himself, and the rabbit had a tagline that could be used to describe Kelly to a T: “All I did was plan ahead.”

The G. Lombard Kelly Lectureship

The G. Lombard Kelly Lectureship is an annual lecture, coordinated by graduate students in the Department of Cellular Biology and Anatomy and featuring leaders in the field of science.

Past lecturers have included Dr. Krzysztof Palczewski, Irving H. Leopold Chair of Ophthalmology and Distinguished Professor, Ophthalmology, School of Medicine, University of California, Irvine, a member of the National Academy of Sciences whose discoveries about the properties of a photoreceptor protein have profoundly increased understanding of the molecular basis of vision, as well as Dr. Andrew Fire, professor of pathology and genetics, Stanford University School of Medicine, who won the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine, along with Craig C. Mello, for their groundbreaking work in discovering RNA interference, a fundamental mechanism for controlling the flow of genetic information.

—–

To help continue the teaching legacy of Dr. G. Lombard Kelly,

supporters may give to the lectureship in his name,

at mcgfoundation.org/drglombardkelly,

call 706-721-4001 or email philanthropy@augusta.edu.