Physicians at the Medical College of Georgia and Georgia Cancer Center are working to expand treatment options for people with recurrent cancers — offering a therapy that helps their own immune system fight it off, restablishing a pediatric bone marrow transplant program and celebrating an important milestone for its adult counterpart.

In May, the first patient at MCG and its teaching affiliate AU Health System received CAR T therapy, which essentially reprograms someone’s own immune system to fight off their cancer.

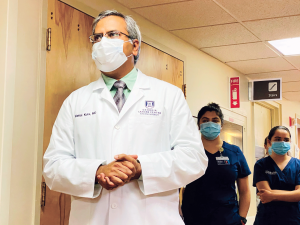

The therapy, used when other traditional treatments like chemotherapy and radiation have failed, was first approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2017. In 2018 MCG recruited hematologist/oncologist Dr. Vamsi Kota to direct its Adult Bone Marrow Transplant Program and to build a CAR T therapy program in Augusta. (The COVID-19 pandemic delayed its launch until 2021.)

“The immune system has the potential to overcome a tumor’s resistance to treatment,” explains Kota, who completed his hematology/oncology training at MCG in 2007. In these cases the immune system needs help. So T cells are removed from a person’s body, then sent to a lab where they are modified to make chimeric antigen receptor, or CAR T cells, engineered to give the immune cells enhanced ability to target a specific protein, like those expressed by cancer cells. Once a large collection of CAR T cells has been created, they are transfused back into the patient’s body. Not only do the CAR T cells kill cancer cells, but they also program the immune system to better recognize the tumor and prevent any future growth.

Burl Webnar of Greenwood, South Carolina, who has mantle cell lymphoma, a rare but aggressive form of nonHodgkin’s lymphoma, was the first to receive CAR T cells at AU Health on May 10. The team has done treatments for four more patients since.

The treatment is not without risks, including the possible rampant release of cytokines, which can provoke an overreaction of the immune system, or brain inflammation caused when immune cells travel there in mass. Those are complications that physicians are still learning to prevent, Kota says.

“Still, I am excited about the potential that CAR T therapy could hold for patients who have failed other forms of treatment and have compromised immune systems,” he says. “I’ve been consistently amazed by the commitment of the entire team here in working to bring new therapies to our patients. We should never forget that helping patients heal is the reason we get up and come to work every day.”

Providing more options for children closer to home

In June, Dr. Amir Mian was named chief of the Division of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology in the MCG Department of Pediatrics.

Mian is working to re-establish a Pediatric Bone Marrow and Stem Cell Transplant Program at the Georgia Cancer Center and the Children’s Hospital of Georgia. The transplants, which infuse healthy blood-forming bone marrow cells to replace diseased ones, have become standard treatment for many children’s cancers like leukemia and lymphoma that tend to recur, for severe immune diseases and more increasingly in patients with sickle cell disease. Currently, if a child needs a stem cell transplant, they and their family must travel to Atlanta, Philadelphia or Cincinnati to get it, Mian explains.

The former interim medical director of the Bone Marrow Transplant Program at Arkansas Children’s Hospital in Little Rock is working to rebuild a robust clinical and research program that treats children and adolescents and complements the well established Adult Bone Marrow Transplant Program at the Georgia Cancer Center. As part of that, he will seek program accreditation from the Foundation for the Accreditation of Cellular Therapy, or FACT, the internationally recognized standard for hospitals and medical institutions offering stem cell transplants. He hopes to have the program established in the next few years.

Mian also wants to develop a CAR T therapy program for hematological malignancies in children and adolescents and develop a transplant immune biology research program in collaboration with other MCG clinicians and basic and translational scientists.

As a long-term goal, he hopes to also develop an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education-accredited three-year pediatric hematology/oncology fellowship training program that consists of one year of clinical training and two years of research.

An important milestone

The Adult Bone Marrow Transplant program at MCG and the Georgia Cancer Center celebrated its 1,000th transplant in August when Lauren Jackson, 35 of Savannah, underwent a transplant to treat her non-Hodgkins T-cell lymphoma.

The MCG Bone Marrow Transplant Program was started in 1997 by Dr. Anand Jillella, now chief of the MCG Division of Hematology/Oncology. The first transplant, an autologous procedure that uses a patient’s own bone marrow stem cells as opposed to a donor’s, was performed on Wanda Attaway of North Augusta to treat her breast cancer. Attaway is still doing well.

“Transplant is a complex process involving multiple teams working together. A number of 1,000 shows that we have all of these teams working together for all these years and helping their patients through that time,” says Kota, who now leads the adult program.

Jackson, whose lymphoma initially responded to chemotherapy but then returned, had her blood stem cells removed, then took a high dose of chemotherapy to kill off her diseased bone marrow.

Then a week later she received her own filtered blood stem cells back with the hope that they would restore her body’s ability to make new healthy bone marrow, which includes cells that help build a better immune system that can fight off infection.

After the transplant, she moved into isolation to give her transplanted stem cells time to work and build a new immune system. While it can take months or years to fully recover from a bone marrow transplant, at press time, Jackson was still doing well.