The rich history of the College of Nursing has seen change and rapid growth with an unbroken tradition of excellence, innovation and service.

It was the late ’60s, and on the surface at least, the MCG School of Nursing was little changed since its relocation from the University of Georgia to Augusta in 1956. The program was still relatively small, and female nursing students even remained garbed in prim and proper white nursing uniforms and traditional peaked cap, complete with a black stripe to mourn nursing icon Florence Nightingale.

But it wasn’t called the “Turbulent Sixties” for nothing. There was an undercurrent of change that would explode as the decade turned. In fact, throughout the rich history of today’s Augusta University College of Nursing, change — marked by rapid growth — has been its most consistent story.

‘A Very Different World’

Alumni will well remember Dorothy “Dottie” White, who became dean of the MCG School of Nursing following E. Louise Grant’s 20-year tenure (1951 to 1971). Lenette Burrell, a former professor at the satellite branch in Athens, recalls White as a presence with a capital P: “She was six feet tall and about 250 to 275 pounds, and she had an expressive voice. … When she came in, people looked up to her.”

White was tasked with growth, and grow the school she did. Gerald Bennett and his future wife, Sharon, were both students at the SON at that time and taking prerequisites at Augusta College. “It was a really interesting time,” said Bennett. “It had recently been a very small program, but when we came, Dottie White was the dean, and she had transformed the Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) Program to be remarkably larger when over 300 new BSN students were added in 1973.”

For Sharon Bennett, the season of change was perhaps most visibly marked by updating the image of nursing and expanding the roles of nurses in health care. “We as a class were very opposed to having to wear those nursing caps,” she recalled with a laugh. “Nursing students had been required to wear dresses or skirts. We considered that to be very uncomfortable to have to work in — and sexist. We had men in our class, and we needed a unisex uniform. I remember writing articles for The Cadaver [MCG’s unofficial school newspaper] expressing what my peers were saying about how ridiculous it was to hold onto outdated views of nursing. Thankfully, our School of Nursing faculty and Dean Dottie White listened to us, agreed and were strong advocates for the modernization of nursing.”

As enrollment grew, the SON and MCG became home to a group of students with far more diverse backgrounds, nationalities and geographic locations, reflecting what was going on in society as the Vietnam War was ending, the Civil Rights movement was in full force and migration to the Sunbelt was taking place nationwide. “There were increasing expectations for MCG to be changing and becoming more of a national university,” recalled Gerald Bennett.

New Programs

But increased enrollment wasn’t the only change that occurred. Part of the change strategy included adding and adapting new programs; for example, a master’s in nursing (MSN) program joined the Baccalaureate in Nursing Program in 1968.

Burrell remembers it well. At that time, most nurses graduated from diploma programs and earned baccalaureates in other fields. Yet a BSN was required for admittance into an MSN program. It was a classic catch-22.

So Burrell pushed for change. She had already earned a bachelor of social science from Georgia State College for Women while teaching a practical nursing program in Milledgeville and raising four children with her physician husband. But what she really wanted was a master’s in nursing. With permission from Dean E. Louise Grant (and after passing an exam in medical-surgical nursing with a grade of B), she was able to enroll as an affiliate in the MSN program. And when Dottie White took up the deanship, Burrell went to the dean’s office once again to explain her situation and to lobby for many other nurses who were in her position.

White was intrigued. “Dean White said she would send [my] information to the Georgia Board of Regents to show the need to change the admission requirements for the MCG School of Nursing master’s degree. This was done,” said Burrell. “So the master’s program became open to a nurse who had a diploma and a bachelor’s degree and was working in nursing. … They really increased their growth then.”

In May 1972, Burrell became the first nurse without a BSN to graduate from the MCG School of Nursing with an MSN, with her family present and applauding as she walked across the stage. But it wasn’t to be her last “first.” White offered her a position teaching BSN classes for MCG in Milledgeville. But before classes could even start, Burrell’s husband, Zeb, was offered a position as medical director at Athens General Hospital.

Burrell contacted White immediately, who suggested she talk to someone in Athens about a possible collaboration with the MCG School of Nursing in Augusta.

A satellite in Athens wasn’t such a stretch. After all, the nursing program at MCG had its roots there. Meanwhile, according to Burrell, the only nursing education in Athens at the time was a practical nursing (LPN) program.

Response to Burrell’s inquiries was enthusiastic and immediate. The University of Georgia, Athens General Hospital and St. Mary’s Hospital all came on board, along with other health-related organizations — and registered nurses throughout the area clamored for the ability to earn a BSN in nursing right in their own hometown.

Burrell’s first office was a made-over patient room at Athens General Hospital, and the first classroom was just a meeting room with plenty of chairs for the 25 to 30 students who enrolled. As the satellite grew, the site moved up and down Milledge Avenue, recalled Burrell, until it moved into a shopping center. “It was a Piggly Wiggly,” said Burrell with a laugh, “and my office was in the produce section where they used to have fruits and vegetables. … The college is still there — and now offers doctoral-level courses in nursing.”

Growing Side By Side

Meanwhile, up the hill, Augusta College was feeling its own growing pains.

Coinciding with the discontinuation of local diploma programs in nursing — the Barrett School of Nursing and the Lamar School of Nursing, both supported by University Hospital — the Board of Regents approved an associate degree program in nursing to launch at Augusta College.

For nursing educator Connie Skalak, who was chairman of adult nursing, had taught medical-surgical nursing at the MCG SON for six years and had helped launch the master’s program, the associate program was an opportunity for shorter days and summers off so she could spend time with her two young children. So when AC Nursing Chairman Louise Bryant invited her to help start it, she embraced the opportunity.

Her first office was just a basement room (“with pipes above my head”). But there, she wrote the program’s conceptual framework and philosophy, and she typed the first National League of Nursing accreditation study. “I never will forget it,” said Skalak. “Linda Dunaway and I both could type really well. And, of course, we had old typewriters back then — we didn’t have any autocorrect. So we would be at the hospital from seven to noon in the morning, and we were at the Department of Nursing until 6 o’clock at night still typing.”

The accreditation study was submitted, followed by an on-unit site visit with the first class of nursing students. Skalak remembers priming her 10 students to “act intelligent” and ask questions. But when she went to look for them, “They went and hid!” said Skalak with a laugh. “They got scared, and I found them in the staff bathroom. So I said, ‘Y’all get out there and talk with Jerry; he’s a nice guy.’ And then they did and they really liked him and he liked them and it all worked out great. We went through all the accreditation with flying colors.”

Skalak said that from the beginning, the AC associate program and MCG baccalaureate program never felt like competitors. “I advised a fair number of students to go to MCG rather than coming to us, because I felt like that was where they needed to go.”

‘A Time of Stability’

Back at the MCG SON, the cycle of rapid growth in the 1970s was followed in the 1980s by an emphasis on achieving higher levels of academic excellence. Gerald Bennett, who returned to MCG in 1983 as a faculty member, recalled, “It was a time of stability. Mary Conway was the dean … and she had a very clear focus, which was to include more scholarship and research in the school for students and faculty and to overall enhance the educational environment — as should be the case in a school of nursing that’s in an academic health center

like MCG.”

The National Institutes of Health had at that time started a National Center for Nursing Research (today known as the National Institute of Nursing Research), and Conway was determined that her nurses would be prepared to meet the demands of this new generation of nursing research. Dr. Marion Broome was then a faculty member at the SON, and Conway tapped her to build a new program, provide faculty with the resources and critiques they needed to write strong research grants and, most of all, to provide encouragement.

“If you asked me who the most important mentor in my entire career was, it was Mary Conway,” said Broome, who today serves as dean of the College of Nursing at Duke University. The year and a half she spent building the Center for Nursing Research at MCG challenged Broome and taught her valuable lessons she takes with her to this day. “That was my first evidence of ‘systems thinking’ actually, now that I look back, [and today] it’s my real go-to strategy.”

The strong sense of collaboration supported by a collegial and encouraging family atmosphere is what Sandy Turner remembers, too. Like Broome, Turner was tapped to help start a new program thanks to changes on a national level. A growing physician shortage was leading to a call for nurse practitioners, so MCG decided to revisit the program (a nurse practitioner (NP) program had briefly been available in the ’70s).

Program leads worked closely with Emory University, which had a program already in place, to develop the curriculum, but with one important change: MCG’s model would offer modules in adult, pediatric and geriatric care. This was a unique concept and an improvement on current practice, which was typically disease- or lifespan-based.

“It was interesting,” said Turner. “It was a fun time trying to come up with some creative things.” With few NPs available to teach the program, Turner relied on physicians as well as NPs from other schools to serve as guest lecturers. To learn about lab values, the program collaborated with the College of Allied Health Sciences so students could peer into microscopes to examine red blood cells or work with radiology to learn how to read simple X-rays. “We spent a lot of time working with students so they could learn how to become experts on their own.”

The challenge looming over all this was that Georgia remained the only state in the nation where NPs weren’t able to prescribe medication. Although NPs might graduate from MCG, many were then going outside the state to practice.

So in between teaching classes, Turner and other local nurses wrote letters, lobbied for support and reached out to legislators to educate them on why it was important for NPs in Georgia to have the right to prescribe. It took the support of physicians — and the Medical Association of Georgia — along with nurses being elected at the state level, but 10 years after MCG’s NP program was launched, NPs were finally given the right to prescribe. After all her hard work, “I was able to be there when they signed the bill into law, so that was very exciting,” said Turner.

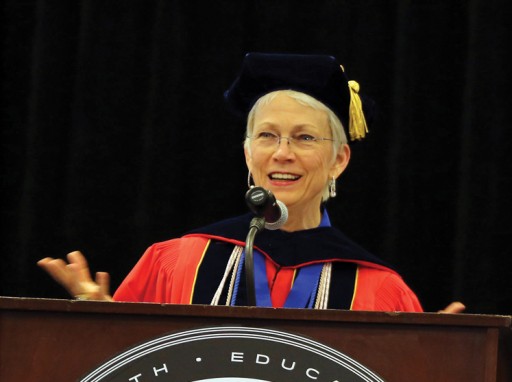

The Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) Program soon followed, thanks to new Dean Lucy Marion, who stepped into the role in 2004. Turner assisted on that project, too, and taught the first class, all faculty members. “I had to drag some of them kicking and screaming through the program,” Turner remembered with a smile. “It was intense at first. I had one faculty [member] … I went in her office and she took her books and she threw them in the trashcan and she said, ‘That’s it! I’m not doing this anymore.’ I pulled the books out of the trashcan, and I said, ‘Now listen, you’ve gone this far, you need to finish.’”

The Continuing Story

This year, the DNP Program celebrated its 10th anniversary. And in 2015-16, there are three major milestones: the 10th anniversary of the master’s-entry Clinical Nurse Leader Program (unique to the CON); the 20th anniversary of the Nursing Anesthesia Program, which remains the only such program in the state; and the 30th anniversary of the PhD Program, which was launched by Dean Mary Conway.

Today, Marion likes to walk on the fifth floor of the Health Sciences Building at Augusta University, where a timeline of the College of Nursing winds its way down a long hallway. Above and below a painted black line are photographs, mementos, newspaper clippings and placards delineating the CON’s rich and diverse history. Since the first class graduated in 1958 — many of whom remain active alumni — the CON has undergone multiple transformations, faced numerous challenges and upheld its mission to meet the ever-changing needs of patients and health care as a whole.

Not the least of which was the consolidation of the MCG/ GHSU and ASU nursing programs in 2012 — whose motto was “We believe … we all belong.” And today, after the two halves have found synergies to form a greater whole, the story is still being written. “If you’re going to stay out there in front, you have to be willing to make change and hold onto the valued part of the tradition — excellence, innovation and service,” said Marion. “It’s not a rollercoaster; it’s progress. Progress is not even. It’s start and stop and sweat and then cooling off. … It’s really hard to go through change without some pain, but we’ve worked very hard [to be where we are now]. We are proud to have legacy institutions that fed into us; some are still our partners, and we do believe that we’re carrying the torch for all of us.”