Retired Biochemist Has Song in His Heart

A lifetime of education notwithstanding, he felt decidedly intimidated recently during a Shakespeare course.

He enrolled in the Augusta University course as one of his many retirement pursuits, thinking he had a respectable enough familiarity with the bard to hold his own, even among a class full of English majors. But when the professor asked the class to opine about Lady Anne Neville’s attraction to Richard III, Bustos sat in petrified silence as his classmates waxed eloquent with interpretations and allusions attesting to a seemingly much deeper knowledge base than his own.

“I stayed quiet and hoped the teacher wouldn’t call on me,” Bustos says with a laugh.

No such luck. So when pressed for his opinion, Bustos decided to draw on his basic-science expertise. “I mentioned that in addition to being a case of a simple hormonal storm, Lady Anne’s feelings could be explained by the fact that the love and hate brain centers are in close proximity and share the same circuitry,” he says. “The class seemed impressed, and that gave me so much confidence. Before the class, all I’d been able to do was drop a few Shakespeare quotes into conversations.”

Opening Doors

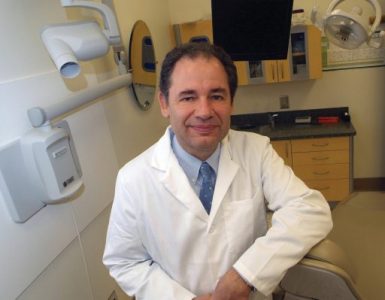

The anecdote, which Bustos shares with his characteristic sparkling wit, speaks volumes about the man who served on The Dental College of Georgia faculty for almost 30 years before retiring in 1998. For one, he’s remarkably versatile. The Chilean native’s first love was linguistics (he studied three languages by his teens and is still adding to his repertoire), but chose dentistry as a vocation when encouraged to pursue a more practical path and embraced it with gusto. For another, Bustos is a lifelong learner who always welcomes new challenges. It was in retirement, for guitar (he’s an amateur guitar performer at the North Carolina Jazz Festival), and his boundless curiosity opens new doors on a virtually daily basis. He also cheerfully acknowledges his limitations while not letting the fear of failure deter him from trying new things.

For instance, “I took an art class and realized that was not something I would be very proficient at,” he concedes. “It took me forever to finish a project.”

But modesty notwithstanding, there’s not much Bustos isn’t good at.

His high-achieving nature was evident early on. He grew up drinking in his mother’s loves of literature, languages and music. “She taught me nursery rhymes in English, and she was a Conservatory-trained pianist who could play any piece at first sight,” Bustos recalls fondly. His youthful pursuits included reciting Walt Whitman poetry flawlessly in his school auditorium, competing with indefatigable tenacity on a rowing team and playing guitar and bass in a jazz combo. His potential seemed as boundless as the view from his childhood window, overlooking the Maule River feeding into the Pacific Ocean. He has no qualms characterizing his youth as nothing short of charmed. His education, he says, was second to none, and Chile at the time was “an island of democracy.” Anything seemed possible, and Bustos was determined to take advantage of every opportunity.

Heading North

He pursued his higher education at the Universidad de Concepción, where dentistry is considered a specialty of medicine. Earning his dental degree required that Bustos take three years of the curriculum required for medical students. The last three years were devoted to dentistry. “We had to do a hospital internship before being awarded a DDS degree,” says Bustos. “I did mine in ear/nose/throat, which is an integral component of oral health.”

After earning his degree at the Universidad de Concepción, he obtained a faculty position there. He stayed for four years until, in 1962, he received a scholarship to further his studies at the Universidad de Santiago. But soon after his arrival, he was informed he had been accepted for a Fulbright Scholarship at the University of Rochester in New York. “I’d published a paper on radioisotopes, and I was invited there to do research,” he says. “I had applied, but I was astonished when I was accepted. It was extremely competitive.”

So off he went, trading Santiago’s balmy Mediterranean climate for the bone-chilling cold of the U.S. Northeast. But Bustos was single, light on his feet and ready for a new adventure.

He didn’t stay single long. Shortly after arriving in Rochester, he met an undergraduate named Roxann and married her within months. His marital status didn’t diminish his determination to squeeze every ounce of productivity possible out of his Fulbright Scholarship.

“The scholarship enabled me to do research full time, but I wanted to take courses, too, so I took a full load.”

He says with a laugh that he may actually have overextended himself for once — “I learned my lesson” — but he managed to keep all the balls in the air. Bustos returned in 1968 to his faculty position at the Universidad de Concepción School of Medicine Department of Physiology with his family, which now included two daughters and a son. “Immediately, I started teaching and continuing my research on histones,” he says. “I had to gather the necessary lab equipment and collaborators. It required arduous work, tenacity and creativity, but we surged forward and embarked on an investigation of rat and hagfish histones to document any evolutionary changes in these proteins. The research steadily progressed but came to a halt due to the lack of an amino acid analyzer.”

Fortunately, his thesis advisor at the University of Rochester, Dr. Alexander Dounce, suggested processing the histone samples in his lab. “My mother-in-law then invited the rest of the family to Syracuse,” Bustos says, “so we boarded a plane to the States.”

Leap of Faith

It was then that he found out how high the demand was for his considerable skills. He received a call about a possible faculty position at The Dental College of Georgia (then the Medical College of Georgia School of Dentistry). The founding dean, Dr. Judson C. Hickey, was seeking faculty members with both a dental degree and a PhD in a basic science.

“All of the original faculty had dual degrees,” Bustos says. “Although he was not trained as a scientist, Dr. Hickey was quite aware of the importance of the basic sciences in dentistry. He anticipated very early that dentistry in the future would no longer deal exclusively with dental caries and periodontal disease. Instead, its scope would include all the diseases and disorders that affect the oral and maxillofacial structures throughout life. He is quite a remarkable man.”

Bustos was high on his wish list for the Department of Oral Biology faculty.

Bustos agreed to an interview but acknowledges he had second thoughts upon flying to Augusta for a recruitment visit. “I remember flying into town, and I couldn’t see any streets from the plane — just woods,” he says. “And when I was being shown around the city, I couldn’t find a library. I went home and told my wife, ‘I don’t think they have one.’”

Hickey offered him a faculty position, but Bustos declined. “I wrote to Dean Hickey about my decision, and he sent me an extremely nice letter saying that if in the near future I would reconsider my decision, to please let him know,” Bustos says.

Shortly afterward, the family returned to Chile. “Unfortunately, the political situation had deteriorated to the point that it began to interfere with my academic duties,” Bustos says. “This prompted me to reconsider Dr. Hickey’s offer. Within a few weeks, I took a leap of faith and communicated my acceptance.”

Arriving in Augusta, he was happy to find out the city had plenty of libraries. But he still had last-minute jitters. Frigid late-winter air greeted his arrival, a gloomy omen in his estimation. “I’d brought my whole family here, and all I could think was, ‘What did I do? Did I make a mistake?’”

Music to His Ears

Then, like an oasis in the desert, everything changed.

“It was so cold when we arrived, but practically overnight — spring!” Bustos recalls, his eyes sparkling at the memory. “Flowers were everywhere. It was like an artist had painted the city. It evoked music to my ears. That changed everything.”

He relished starting a school from the ground up with Hickey and his fellow recruits, all of whom were eager to create curricula that provided dental students as comprehensive a basic-science education as the medical students received. Bustos was delighted to discover how committed Hickey was to his faculty. He invited Bustos to design his own lab to his specifications. “Besides being personable, knowledgeable, articulate and caring, Dr. Hickey was a charismatic leader,” Bustos says. “He would stop by my office and ask how I thought he could make the school better. He had tremendous rapport with people. He knew everyone by their first name.”

Bustos’ duties, in addition to teaching dental students, included teaching biochemistry to students in the Medical College of Georgia and other health sciences programs in the university. He served as coordinator of the Department of Biochemistry from 1979 to 1996.

His approach to a medically infused dental education was nothing short of visionary.

It was so cold when we arrived, but practically overnight — spring!” —Dr. Sergio Bustos-Valdes

Close Bonds

“It was clear that medically complicated or compromised patients, especially the elderly, were becoming a larger part of the dental practice,” he says. “Treatment for these patients requires that their systemic health problems are considered. Changes in oral health care have made the acquisition of additional knowledge of these diseases more important.”

He was on the forefront of incorporating those changes in the classroom. He advocated other curricular changes as well. For instance, he pushed for more time for students to integrate basic and clinical skills, favoring problem-based learning to stimulate critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Upon his retirement, he was asked to help facilitate problem-based learning in the Medical College of Georgia curriculum.

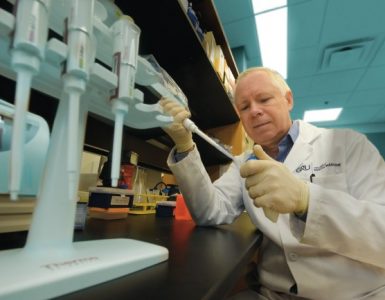

Research also factored prominently in his workload. “I was particularly interested in histones, the proteins that communicate instructions to genes,” Bustos says. “We originally thought the histones just held the DNA together, but nothing could be further from the truth. That study has exploded into a field called epigenetics. I had no idea how important it would turn out to be.”

His broad expertise enabled him to incorporate anatomy, physiology and pharmacology into his lectures. He thoroughly enjoyed the teaching and research roles of his career, establishing close bonds with his students and mentees.

In addition to guiding them in classrooms and labs, he also enjoyed challenging them to the sports he’d mastered in Chile. Little did the unsuspecting students realize that they were playing with a ringer.

“A group of students invited me to play table tennis once,” Bustos says. “I think they thought, ‘We’ll give him some retribution for what he puts us through in the classroom.’ But my spin drove them crazy. They couldn’t get the ball back.” He repeated the same impressive feat with students on the tennis court.

Following His Dreams

His family thrived in Augusta as well. Roxann, who had already earned a master’s degree in English at the University of Rochester, earned a master’s degree in library science at the University of South Carolina and began her own career at Augusta University after the children had flown the nest. She has now retired as an emeritus associate professor.

As fulfilling as Bustos’ life was, he still felt the pull of long-dormant passions. He never lost his love of linguistics and wanted to learn still more languages. He wanted to supplement his love of literature with more education. He wanted to immerse himself further in the music he loved.

He retired in 1998 to follow those dreams, virtually all of which he has fulfilled — and then some. “I go to bed thinking about music and I wake up thinking about music,” he says. “And I’m becoming increasingly proficient in languages, including Italian, German and French. I’m not interested in just being able to say, ‘Hello, how are you?’” At this time, he is enrolled as a first-year piano student in Augusta University’s Department of Music and in three online courses.

His scientific expertise has also continued to be in high demand. For instance, upon his retirement, he was asked to chair the Savannah River Site Health Effects Subcommittee, an independent group of citizens charged by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to study the effects of radiation on citizens who live near nuclear plants.

The Beauty of Retirement

The beauty of retirement, he noted, has been the ability to pursue as many disparate passions as he pleases.

This has included traveling extensively with his family, including his grandchildren. Five of those grandchildren live next door and frequently enlist their grandfather in passions of their own. During this interview, for instance, his grandchildren, Ben and Clara, had manned a lemonade stand in their front yard, calling over to him to lend a hand. Odidi, as they affectionately call him (pronounced O-Dee-Dee), was more than happy to oblige.

At age 84, Bustos looks fully three decades younger and has more energy than most people half his age.

When he retired in 1998, he noted, “I have ambitions I have not fulfilled.” Almost 18 years later, he is thrilled to have marked many of those items off his bucket list — and even more pleased that plenty still remain.

“Says Bustos simply, “I’m very enthusiastic. I approach everything I do with zeal.”