Gov. Nathan Deal was moved by stories of children in Georgia who suffered daily with intractable epilepsy, or epilepsy not controllable with medication. Children like then-7-year-old Preston Weaver of Augusta, who at the time was experiencing up to 100 seizures a day from a severe form of epilepsy called Lennox-Gastaut syndrome.

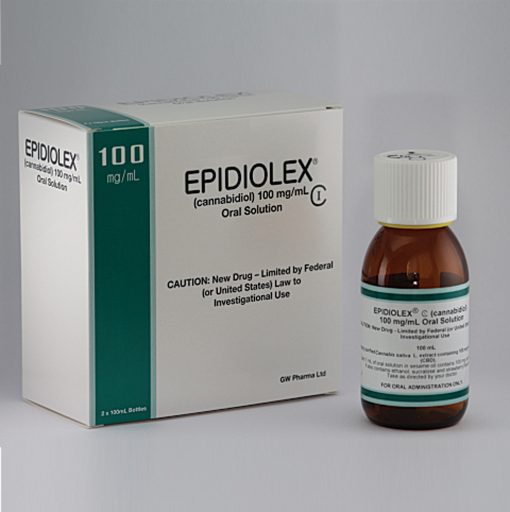

The governor wanted to find a way to safely treat these children with cannabidiol, a chemical compound found in cannabis, while contributing to the science that could ultimately lead to a prescription medication. Cannabidiol had shown promise, but clinical research had not proceeded far enough for U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval. More research was needed, but in the meantime, children were suffering.

As the state’s public academic medical center with a strong research infrastructure, Augusta was the perfect institution to both provide treatment and conduct research on the safety of cannabidiol use. However, the governor left the “how” and the “who” to the university.

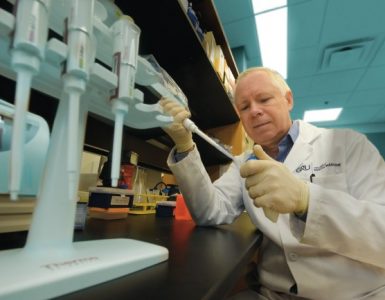

The “who” was easy: Dr. Yong Park, director of the Pediatric Epilepsy Program at Augusta University. Park is an authority on the treatment of childhood epilepsy.

Park had already been looking for new treatment options for his patients. He was seeing the same patients again and again, but current medications were not effectively controlling their seizures. This led to Park’s interest in being part of a research study with cannabidiol.

“This research study is a chance to provide purified cannabidiol to populations that are in need of medicine,” he said. “These patients may not have another option.”

In order to gain access to cannabidiol, the university reached out to GW Pharmaceuticals. The company had already developed Epidiolex, pharmaceutical-grade cannabidiol, which had been approved by the FDA for use in ongoing clinical research trials, but not yet approved as a treatment. In May 2014, a little over a month after the initial call, Augusta University, GW Pharmaceuticals and the state of Georgia signed a memorandum of understanding to provide treatment to children with Epidiolex. GW Pharmaceuticals agreed to provide the drug at no cost to the state’s study, while the university was tasked with developing and managing the study and collecting treatment data regarding the safety and efficacy of cannabidiol.

In order to make the study available to citizens throughout the state of Georgia, Park recommended establishing partner sites in both Savannah and Atlanta, with other pediatric epileptologists, an approach that would benefit from Diamond’s experience administering multicenter research studies.

“The specialty of the physician is particularly important from the perspectives of the Food and Drug Administration and the Drug Enforcement Administration, because both entities have to determine that the doctor is qualified to run this study,” explained Diamond. “It is a common misconception that cannabidiol is legal, but as a compound from cannabis, the DEA classifies this cannabidiol as a controlled (schedule 1) substance. Dr. Park and each of our partner physicians had to receive federal approval and obtain a DEA Schedule 1 license, which is above what is normally required.”

After figuring out “who” and “where,” the next step for Diamond and Park, along with their teams, was months of writing the study protocol, the research equivalent of laying groundwork. They determined the study would be an expanded access protocol, also called “compassionate use” protocol to meet the governor’s aim of providing treatment to as many children as possible who could potentially benefit from treatment.

Nearly six months later, Diamond, Park and their teams finished the study protocol, a feat in itself. The normal time frame for establishing protocol for a trial of this caliber can be several years, according to Park.

Georgia was the first state in the country to open a state-funded expanded access program, and Augusta University was the first open study site. It’s a novel approach, according to Diamond. Normally, studies are done through pharmaceutical companies and contract research organizations. In this way, the state is funding the study, Augusta University is managing it, and the university is home to a study site.

This approach is now being used in other states, and Diamond hopes this experience opens the door for more research collaborations in the future.

“Being first up at bat has resulted in other states contacting us for suggestions, guidance and input in how they approach programs within their state,” Diamond explained.

“I saw this as an opportunity to demonstrate, in a project that would be very visible, the great research work that we can do at Augusta University,” he said. “Hopefully, this will lead to other situations where companies that have a drug or device or biologic will think about us as a site to conduct clinical trials. This is also providing educational opportunities for students on research in general, but especially cutting-edge research. Hopefully, this opportunity turns some of our students into researchers.”

In the two years since Park has begun conducting the cannabidiol study, 52 children have enrolled with 48 still continuing to receive treatment. All who remained have completed at least one year of treatment, and 50 percent of them have completed at least 18 months of treatment.

The study is ongoing, so researchers still don’t fully understand the benefits of using cannabidiol to treat intractable epilepsy. However, GW Pharmaceuticals continues to conduct randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled trials, which are needed for the FDA to approve cannabidiol as a treatment. Early results from GW Pharmaceuticals’ clinical trials show that many children are experiencing a benefit from treatment with cannabidiol.

“The data doesn’t show a total elimination of seizures, but does show a reduction in frequency for some of the children,” Diamond said. “That’s very consistent with our observations in the patients Dr. Park has been seeing. We also hope that the safety data collected from Georgia’s study will contribute to the FDA process for approving cannabidiol as a new prescription drug so it becomes like any other drug you might get at the pharmacy,” Diamond said.

A Child’s Hope

At 7 years old, Preston Weaver was prescribed approximately a half-dozen medications, one of which has been compared to heroin for its addictive nature.

Doctors were hoping these medications would relieve Weaver’s suffering. He was diagnosed with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, a type of epilepsy that accounts for only 2 to 5 percent of childhood epilepsies. It is hard to treat, and many times seizures are not responsive to medication.

Weaver’s seizures were not responsive to his medications. Once a child who could swallow and speak unassisted, Weaver had regressed to being tube fed and was almost nonresponsive. He was suffering up to 100 seizures a day.

But there was still hope in the form of cannabidiol and in Dr. Yong Park, Weaver’s physician and the director of the Pediatric Epilepsy Program at Augusta University.

Park is the lead investigator in the Georgia Cannabidiol Study at Augusta University. The study aims to monitor the effects of cannabidiol in an attempt to determine the drug’s potential in improving the quality of life for children with incurable epilepsy.

Weaver was the first patient enrolled in the study. The study has since enrolled 52 children and only four have dropped out, a notably low dropout rate.

As the first patient in Georgia to receive the cannabidiol treatment, Weaver’s story made headlines from Atlanta to New York City.

The exposure increased awareness of childhood epilepsy and the use of cannabidiol as a treatment option.

A year after enrolling in the study, Weaver is now receiving the maximum dose of cannabidiol. And it’s making a difference.

Now, Weaver experiences seizure-free days. He is smiling. He is responsive. Sometimes, Weaver talks. [/su_note]Park and physicians at the partner sites are also measuring quality of life to assess the potential impact on quality-of-life improvements experienced while patients receive cannabidiol treatment.

“We have taken extensive surveys of these patients over time to look at whether the patients have quality-of-life outcomes that can be improved by exposure to the study drug,” Diamond said. “Improvement of quality of life is important for these kids.”

As study participants continue to be exposed to cannabidiol, Park is beginning to observe these quality-of-life improvements in many of them.

“Seizure-free days are occurring more often,” he said. “The children are becoming more active. They are more alert and are moving further toward the next step in the stages of learning.”

Cannabidiol trials at Augusta are ongoing, and it appears that treatment with cannabidiol may be a new and reasonable option to effectively treat children with epilepsy. At the very least, Park’s patients seem to be improving their quality of life.

Because of this unique research partnership between GW, Augusta and the governor, residents of Georgia were provided with a new option for treating epilepsy that had never been accessible to patients and families within the state. “We are leaders in providing information to Georgians,” Park said. “We are the Medical College of Georgia, and we represent our state, so we have a responsibility to be involved in groundbreaking research. When the governor asked, we were ready.”