A son remembers his father and his life’s work caring for the people of Zimbabwe.

BY MARK L. RANDALL, MD

One day in the late 1990s, a driver approached a police roadblock. An imposing police officer read the name, Maurice L. Randall, on the Zimbabwean driver’s license and carefully examined the picture and driver. “I know you,” he exclaimed excitedly, “You are the most wanted man in Zimbabwe.”One day in the late 1990s, a driver approached a police roadblock. An imposing police officer read the name, Maurice L. Randall, on the Zimbabwean driver’s license and carefully examined the picture and driver. “I know you,” he exclaimed excitedly, “You are the most wanted man in Zimbabwe.”

How had it come to this?

When Maurice graduated from Lavonia High School with a goal of entering medical missions, his classmates had given him a small straw-hat replica titled, “To keep from baking your brains out in South Africa.”

After graduating from Mercer University in 1961, Maurice vividly remembered his first day at the Medical College of Georgia, where he was told to look at the person on his right and left and that one of the three would be gone by graduation as the work was so challenging. His OB rotation was especially challenging as his wife went into labor on Christmas Day with their firstborn. Since his OB professor was supposed to deliver her, Maurice was reluctant to call him on Christmas Day until he was absolutely certain that it was real labor. His wife never forgot that.

When he graduated from MCG in 1965, Maurice was very proud of his MCG ring. His wife didn’t like the skull and crossbones. She especially didn’t like the fact that he was able to keep up with that ring for the next 50 years, although he lost three wedding rings in the OR.

After his internship in Macon, Uncle Sam made him an offer he couldn’t refuse. For the next three years, Maurice was on the orthopaedic ward of 106 General Hospital in Tokyo, operating on hundreds of wounded soldiers. After a year and a half of surgery residency in Chattanooga, he finally was able to answer God’s call to medical missions and went with his wife and four children to Sanyati Baptist Hospital in Rhodesia (Zimbabwe).

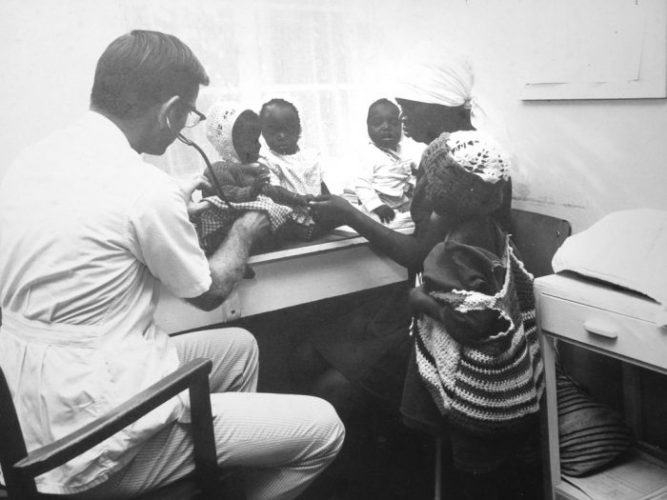

This 100-bed hospital, on a mission station two hours by dirt road from the nearest town, served the many needs of the Shona people in the northwest part of the country. Maurice worked with two other doctors, rounding and operating in the morning and seeing about 200 patients in the afternoon. The goats liked to come in and sleep on the cool concrete under the patients’ beds. This bothered him, and one day he became so frustrated, he grabbed a rock and threw it at a goat that wasn’t leaving fast enough. It ricocheted up and shattered the plate glass window at the nurse’s station. After this, Maurice gave his children 25 cents to chase the goats out.

Medicinal supplies were always scarce. At times his children became frustrated with him when he took down the rope from their tire swing to use for putting patients in traction by hanging buckets of sand off the end of their beds. Finally for his birthday, they gave him a hundred feet of rope and asked him to leave their swing alone.

The civil war came closer to Sanyati in 1978, and Maurice started seeing more gunshots and traumatic wounds from grenades and landmines, along with the usual snakebites, crocodile attacks and ox cart accidents. In July 1978, after operating one evening, he came out to the news that there were strangers on the station and that a co-worker, Archie Dunaway, was missing. The army couldn’t come out that night as it wasn’t secure, so the national pastors came and gathered with the missionaries to pray as 20 missionaries had already been killed that month alone. In the morning, they found Archie’s bayoneted body at the back of the hospital and elected to leave the station.

Maurice and his wife met with their four children and offered them the choice to stay in the country or return to the United States. They all agreed to stay. From the nearest town, Maurice and the dentist drove to the station twice a week in a landmine-protected ambulance until a police convoy was destroyed on the dirt road. Then they flew in a Cessna twice a week for two years. Once the plane landed with a bullet hole through the wing.

After the war ended, his family returned to the station, and Maurice continued to treat the many sick as the only doctor and now administrator of the hospital.

Shortly after this, a mysterious “Slims” disease swept through the country and killed many of the young and middle aged, leaving grandparents to raise the young. It was an unknown disease, and a couple of times when Maurice stabbed himself with an interosseous needle trying to get fluids in a pediatric tibia, he considered the risk and wondered about going home. But the needs were great as this was the only hospital for an area of about 500,000 people.

His surgery schedule was completely full six months out, doing everything in general surgery, gynecology, urology and plastic surgery; researching hemochromatosis with liver biopsies; averaging 200 C-sections a year out of the 2,000 annual deliveries at the hospital; and seeing pediatric and internal medicine patients in the afternoon. There was enough work to keep several doctors completely busy, but for many years he was the only one. He was well-loved by the people and given the name of Dr. Sanyati. They would come from hundreds of miles away for medical care.

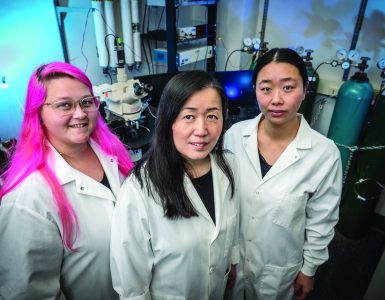

He was patient in teaching many fourth-year medical students who could claim their first appendectomy and C-section under his watchful care. He taught medical students from Australia to Zimbabwe, as over seven different countries sent students to Sanyati Hospital to learn. These students caught his vision and served the underprivileged in Afghanistan, Holland, Morocco, England, Australia, Khazakstan, Uzbekistan, Ireland, New Zealand and Thailand.

Maurice came back to the States in 2001 after 30 years in the mission field and worked in the ERs in Georgia and Alabama for 10 years. He always returned each year for a mission trip to Zimbabwe for as long as he was able as he loved the people very much.

Maurice passed away in July 2016 surrounded by friends and family. His funeral was held in Cedartown, Georgia, streamed and watched in England, South Africa, Australia and Mozambique, while simultaneously a church service was held in Zimbabwe so the people could mourn together their loss.

Even though he was a fellow of the American College of Surgeons, on the board in Zimbabwe, Maurice considered the comment that one of the pastors gave him as one of his highest compliments—“He was a white man, but he had a black heart.”

No wonder my Dad was the most wanted man in Zimbabwe.