Dr. Manuel Pena emigrated from Cuba to the United States when he was just 7 years old.

The young Maya woman was pregnant and had walked four hours over the mountains of Guatemala with her husband and child.

After Dr. Manuel Pena (’81) and his mission team had repaired her child’s cleft lip, through her husband, who could speak Spanish, she asked softly, “Now, can you fix mine?”

With her husband standing next to her and watching, Pena gently numbed her lip, opting out of general anesthesia due to her pregnancy, and performed the repair.

The next day, the family began the long climb back up 9,000-plus feet to their mountain home. “I thought, I’m never going to see them again,” says Pena. “But at the end of seven days, they were back so I could take out their stitches. I thought, this is incredible. This is why I was put here.”

The mountains of Guatemala might have seemed a far cry from the norm for Pena, a Naples, Florida-based plastic surgeon who specializes in aesthetics. But not if you know Pena’s background and childhood. He grew up just across the Caribbean Sea, on the island of Cuba.

While those early years before the rise of Fidel Castro were ones of luxury – Pena was the son of the head of trauma surgery at the hospital in Camaguey, one of the island’s largest provinces – it changed “seemingly overnight,” he recalls. Gone were the cook and the nanny. Gone were the properties, even the family home that had been owned by Penas for over 300 years.

The noose was growing tighter in Cuba. Young Manuel remembers waiting in line with his mother for a ration book that would allow the family to buy basic staples like bread, eggs, sugar or meat as the country’s rich resources were being spent on weapons and elsewhere. Out of fear for their family’s safety, his parents sent Manuel’s sister, then 11, with her godparents to the United States.

The rest of the family fled soon after. “My father and mother and I left Cuba in September of 1964,” says Pena, flying to Mexico where they waited three months for a visa. Then 7, Pena remembers his father taking him to the local pool to swim every day, not knowing that his father wanted him to practice in case they would need to swim the Rio Grande. “He didn’t know how deep it was,” says Pena. “But it didn’t come to that.”

The Penas would land in Miami where the family was reunited. But then came the hard work of rebuilding their lives. His father began the process of being recertified as a physician to work in the United States. And his mother, who had never had to cook or take care of a home and had instead spent her days drawing and playing tennis or canasta, used one of her hobbies to keep the family afloat: sewing. “She was making shift dresses for $1.50 apiece,” says Pena. “It was a sweat shop, but that’s what kept us going.”

It was a tough mountain to climb, but “we were together, we were free and the world was there for the taking,” says Pena.

With the help of friends and the local Boys Club (predecessor to today’s Boys & Girls Clubs), Pena mastered English. After some time in Alabama, the family moved to Milledgeville, Georgia, where his father – now recertified – worked for Central State Mental Hospital and where a large population of Cuban physicians lived. Pena had started working too – even at that young age recognizing the sacrifice his parents had made to ensure their children had a better life.

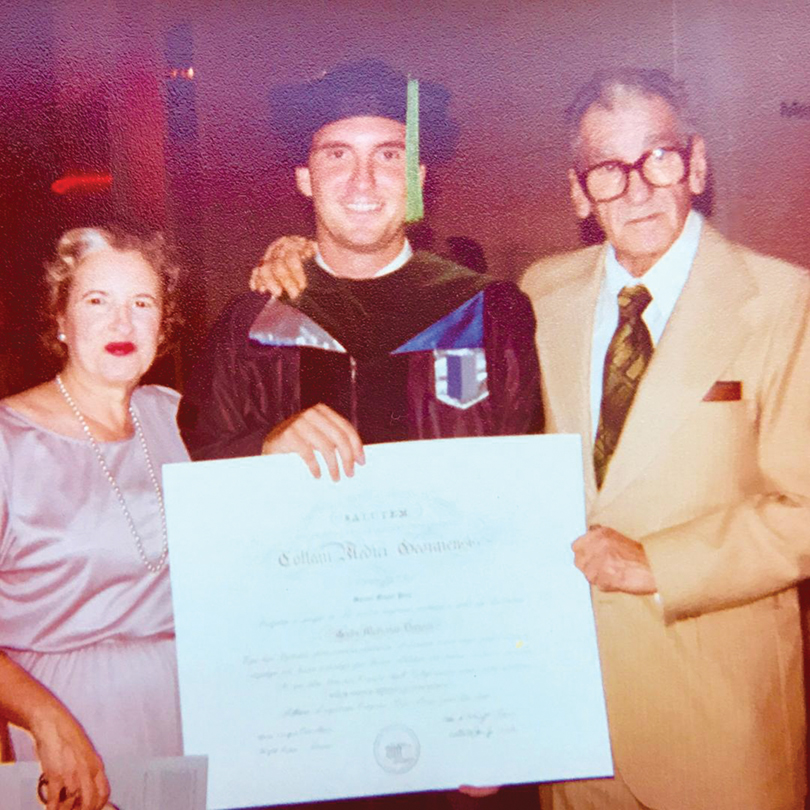

After majoring in chemistry and biochemistry at the University of Georgia, Pena joined the first-year class at MCG, part of a large UGA contingent at Georgia’s public medical school. There was still that college feeling: keggers every Friday night at the cafeteria and raucous homecoming parades (Pena was head of MCG’s Entertainment Committee), but very quickly, he found his life’s work.

The first week of medical school, Pena sat in on a talk by Dr. Kenna Given, who had just been named section chief of plastic surgery. The lecture ranged over everything from congenital defects and trauma to microsurgery and aesthetics. “I didn’t know one field could be that broad,” says Pena. “So after the lecture, I followed him back to his office and said, ‘I want to do this. Will you be my clinical advisor?’ And he said, ‘Sure, I just took over so I don’t know exactly how this works, but we’ll figure it out together.’”

After graduation, Pena completed an internship in New Orleans at Charity Hospital, Tulane University, followed by a general surgery residency at Jackson Memorial Hospital, University of Miami (where he met his wife, Regina) and a plastic surgery residency at the Medical College of Georgia. He also began to start a family, which would grow to two daughters and two sons. Next came fellowships focusing on congenital defects, facial reconstruction and cosmetic surgery at the University of Miami and the Manhattan Eye, Ear and Throat Hospital, an affiliate of New York University.

Pena went home to Florida after his training, choosing Naples as the location for his private practice in 1990 after a chance vacation there and a friend who shared that there was a need for a plastic surgery practice in the area. Life was good, and Pena had already begun giving back to the Boys & Girls Club, which had been so instrumental to him as a new immigrant struggling to learn English. Then Guatemala came calling, thanks to another physician friend who encouraged Pena to clear his schedule and join him for an upcoming mission trip, after the original plastic surgeon had to back out. “I went and couldn’t stop,” says Pena.

Since 1997, Pena has completed nine mission trips, providing major surgical care for more than 250 patients. Along with countries in South America, he has traveled to Jamaica, and Uganda and Burkina Faso in Africa. Back home, he has hosted regular fundraisers such as crawfish boils to raise funds to cover all the equipment and supplies needed. (The boils are ongoing and are now benefiting the Boys & Girls Club of Collier County.)

It’s a need that hits close to home for Pena, who will never forget leaving Cuba, the sacrifice of his parents and the helping hands of so many who have brought him to where he is today. “There’s a great old Chinese proverb. It’s better to light one candle than to curse the darkness. You do just a little bit. That’s all you can do. You can’t fix the world, but if something comes up and you can fix it, you do it.”