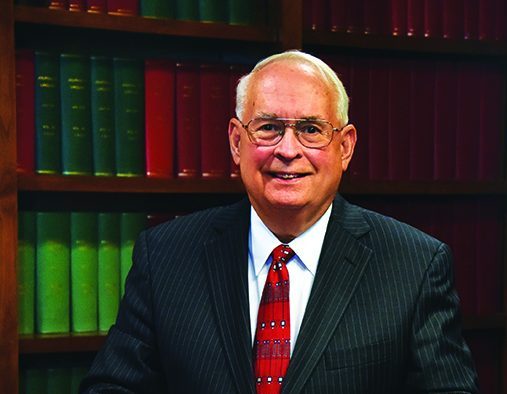

Dr. Ron Lewis always wanted to establish a chair. Now he has, all to support his legacy of teaching.

When Dr. Ron Lewis interviewed at the Medical College of Georgia in 1994 for the job of chief of urology, he was already an internationally recognized expert in sexual medicine and a longtime prostate cancer researcher. He had also served as co-director of the fertility clinic and male sexual dysfunction clinic at Tulane University School of Medicine, vice chief of the medical staff at two Louisiana hospitals, chief of surgery, and a professor and consultant in urology at Mayo Clinic and Medical School.

Chief of urology was supposed to be his next move, but he wasn’t sure he wanted it to be at MCG. “I was kind of a private school snob,” he admits.

But he knew Dr. Roy Witherington, who was chief then and looking for his replacement, and Lewis admired him. “Roy had a very good program,” says Lewis, and after he visited, “Events fell into place.”

Lewis would end up spending 24 years at MCG, more than a third of his lengthy career. During his tenure, he made MCG’s urology resident training program one of the most sought after in the Southeast, if not the nation; and launched a pediatric urology program and a research lab that brought key urological studies to MCG. He’s also left a legacy that’s now been further cemented through his establishment of the Ronald W. Lewis, MD Chair in Urological Education to support the ongoing needs of urology residents, such as education, research, travel, equipment and more.

“When you’ve been in academics as long as I was, you want to leave a legacy. What better way than to do something that involves continual teaching,” he says. “That’s always been a part of my career.”

In practice

The young Ron Lewis might have already known he wanted to teach. But after a particularly rough rotation in general surgery when he was a medical student at Tulane, he was adamant that he was not going into surgery.

Following a rotating internship at the Naval Hospital in Newport, Rhode Island, from 1968-69, where he was exposed to surgery again, he still wasn’t altogether convinced, instead considering seriously both public health and psychiatry.

But he kept going back. “I loved surgery during my internship,” he says. “At Tulane, I also had to do urology, and that was a fantastic rotation.” He enjoyed the variety of it—being able to handle surgeries while also getting to know patients, and the varying organs and diseases urologic surgeons could treat. “I thought, ‘That’s the kind of surgeon I can be.’ So it was rejection, then a conversion.”

As far as conversions go, his was absolute. After completing a residency in urology at the Naval Regional Medical Center in Oakland, California, Lewis spent a couple years working for the Naval Regional Medical Center and Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston before joining Tulane. During his 11 years at Tulane and its affiliated Delta

Regional Primate Center, Lewis took charge of launching several new programs. He started its andrology department to treat male sexual dysfunction and did early work in developing cell culture models of prostate cancer. He also was responsible for launching a national training program based at Tulane for urologists to learn about female urology and incontinence.

When he left Tulane to join the Mayo Clinic and Medical School in Minnesota, the university hired three people to do his job: a researcher, a female urologist and an andrologist. (When he left Mayo to join MCG, it hired two.) “I’ve always been a workaholic,” he says with a shrug.

At Mayo, he came on to replace its prosthetic surgeon, working to provide implants to treat everything from incontinence to erectile dysfunction. “Mayo is very funny,” he says. “When they negotiate with you, they want you to do only one or a couple things.” But Lewis was adamant that he wanted to continue prostate surgery. At that time prior to the PSA test, Mayo had a robust prostate cancer surgery program, averaging about 1,000 radical prostatectomies every year. He also wanted to work in fertility and andrology and made the move to add incontinence surgery.

“When I got to Mayo, I found out the only people who did incontinence surgery at Mayo were the operating gynecologists,” he said. “So I said, ‘Well, that’s not right for residents.’… I had a really good balanced practice.”

Resident training

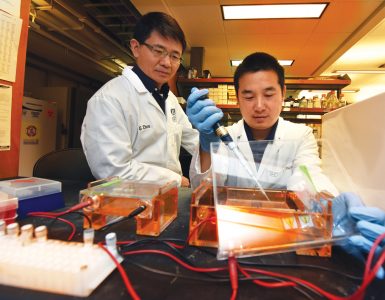

After seven years at Mayo, Lewis joined MCG. During his time here, Lewis founded the region’s first pediatric urology program at the Children’s Hospital of Georgia. He opened a research lab that soon received an NIH grant for prostate cancer research as well as a major Veterans Affairs grant, hiring a researcher from Berlin and next a researcher from Mayo (who later went into administration for the national VA) to lead it. The lab was supported by Augusta businessman Julian Osbon, a pioneer in the treatment of erectile dysfunction, who promised startup funding in return for Lewis’ hire. Lewis also participated in other pioneering research for medical treatments for impotence, including the drug Cialis.

The resident training program at that time was doing all right, but Lewis saw an opportunity to build the program into a regional—if not a national—level program, in demand from applicants both in and outside the state.

His lab would give residents the chance to conduct research—something they’d never had before. He also had a goal to encourage residents to also go into teaching themselves—“and we’ve had really good success with that,” and on top of that, “never losing the reputation of training good urologists,” he says.

In fact, Lewis launched the Monday night conference that continues to this day, in which residents and faculty review cases. It started as a way to ensure that faculty had a good overview of the surgeries being done by residents, but has evolved into an invaluable give-and-take as faculty and residents share their viewpoints of cases and determine together the best path of care for the patient. “The residents can come up with ideas we haven’t thought of,” Lewis says. “That’s the strength of academic programs.”

At that time, the program had only ever graduated one female urologist. “We wanted to open it up, genderwise,” says Lewis. Today, at least one-third of the graduates in the program are women.

And Lewis has met his goal of transforming the resident program. Every year, the urology section receives roughly 200 to 300 applications, and conducts 60 applicant interviews to fill two residency slots, ensuring that MCG’s program trains some of the top residents in the country.

A great journey

Even though Lewis retired officially in 2018 — after stepping down as chief in 2011 — his residents used to have a running joke about the self-professed workaholic: “Dr. Lewis is the only person who’s retired 11 times.” Today, he lives in Marietta, where he remains active in urology, although he no longer practices.

At the time of this interview, he was in Augusta for MCG urology’s Rinker Witherington Annual Meeting. The weekend before, he was at the Cloister at Sea Island, Georgia, speaking at the Georgia Urological Association annual meeting on a guideline statement recently published by the American Urological Association that he helped develop on diagnosis and treatment of testosterone deficiency.

Globally, he spoke on the same guideline for the Canadian Urological Association in Quebec. He also stays active in the International Society for Sexual Medicine, which he helped found. He wrote its original bylaws and remains one of only two members who have attended every meeting.

“In 1978, most of erectile dysfunction was thought to be psychological,” Lewis says. “[But] there were some key breakthroughs.” That year, Lewis joined other world scientists interested in the field in New York City. Slowly, they gathered aninternational group of experts, meeting two years later in Monaco, then Copenhagen, then Paris, then Prague, building the foundation of what would become the ISSM. Over the past 40 years, Lewis has seen the field change tremendously, from a psychological disease to a better understanding of the vasculature of the organ, the value of prosthetics, the impact of other disorders, the use of ultrasound to improve erectile dysfunction, and of course oral therapy, including Viagra and Cialis, both of which Lewis has studied. “It’s really been a great journey to see those things happen over the years,” he says.

A lasting legacy

Through Lewis’ work, many grateful patients have given back to the institution in a number of ways, including supporting buildings and donating much-needed equipment, such as urology’s robotic surgery suite.

Now, it’s Lewis’ turn. “Here’s the thing,” he says. “I always kind of had it in the back of my mind.”

Now the chair in his name will continue to stress the importance of education and what it has meant for MCG’s Section of Urology. That includes former residents who now hold teaching positions of their own, passing on what they learned at MCG—and from Lewis and others—to the next generation. “It’s been a value to me to be able to continue this legacy of education…When Charlie Howell [a ’73 MCG graduate and chair emeritus of surgery] came up with the idea, ‘Why don’t we establish a chair that would just support that educational aspect of residency?’, I just thought it was a super idea, and I said, ‘I’m in.’”

Are you in?

If you’re interested in supporting resident education, research and travel in the MCG Section of Urology, visit mcgfoundation.org and choose to give to the Ronald W. Lewis, MD Chair in Urological Education.