In private practice, he made his impact one patient at a time.

He turned to public health for a multiplier effect.

Then COVID-19 turned it up another notch.

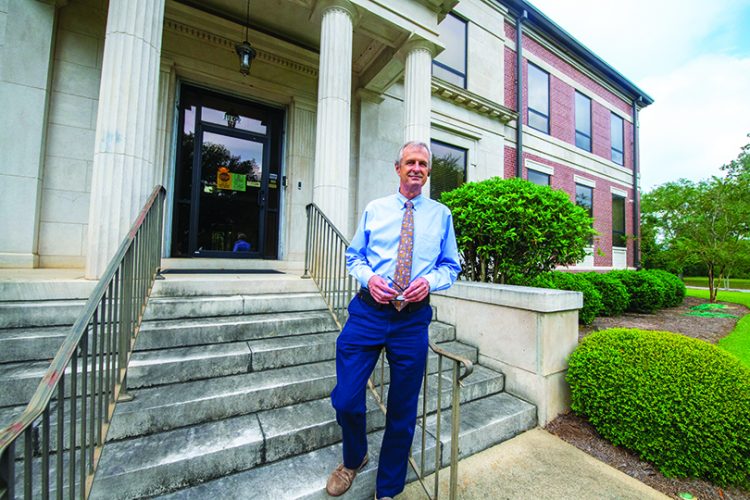

“I thought this position might be a nice change,” says Dr. Charles Ruis, ‘86. “I couldn’t have predicted what this area would face when I came here. I thought the worst would be an influenza pandemic or a tuberculosis problem or something like that. I certainly didn’t envision what we’ve been through,” says the director of the 14-county Southwest Public Health District who has helped lead his community through the worst public health crisis the state and country has ever seen.

Southwest Georgia roots

Ruis has deep ties to Southwest Georgia. A native of Cordele, he grew up idolizing area family physicians like the late 1951 MCG graduate Dr. Perry Busbee. In fact, it was Busbee who submitted Ruis’ name as a possible replacement for him on the Crisp County Board of Health.

“When he retired from practice, he also retired from the board,” Ruis says. “If he thought that I was a good match, I was not going to let him down. That’s how I got involved.”

He says he was fascinated at just how widespread public health’s impact could be.

“It is involved in so many aspects of society and culture,” he says. “Serving on the board sort of opened my eyes. The part of public health where we relate to and serve populations instead of one person at the time really started to appeal to me.”

He says he was in the “last laps” of a career that had seen him practice as a family medicine and emergency medicine physician and, for a time, even as medical director of a hospice program.

When the district health director position became available in 2016, Ruis thought about how much he’d loved his nine years volunteering on the Crisp County Board and jumped at the chance to lead.

From over-prepared to under-prepared

It wasn’t long after he was appointed in 2016 that Ruis began to realize how big a role public health played in emergency planning. They were constantly running disaster preparedness drills and checking stockpiles of things like personal protective equipment. They had full-time staff dedicated solely to emergency preparedness.

“Back then I thought maybe we could have an anthrax situation or something like that and we may need all this preparation, but I had doubts about whether we were over-prepared,” Ruis remembers.

Like the rest of the world, the health care community in Albany and the surrounding area knew that COVID-19 would eventually arrive. But how, when and how many people it would affect in the community, they could have never imagined.

In late February, there were two large funerals held in town. Someone visiting town for those services brought the novel coronavirus with them.

Cases started multiplying in the community and Ruis and his staff were trying to put the dots together. Why was the disease spreading through the community so fast?

A call came from Dr. William Sewell, an OB/GYN who works closely with (recently retired) Phoebe CMO Dr. Steven Kitchen (see page 6), asking him to come to Phoebe’s executive boardroom. “I opened the door and it was like it was incident command. That’s when I knew this was big,” Ruis remembers.

The Phoebe team had begun a list of people admitted with the virus. They had found patterns — people from the same families who lived together and who had attended the same funerals a few weeks before. Ruis had noticed the patterns. It was spreading from family to family.

“Part of it was bad luck. One or two people came into the community early on before we had the knowledge, before anybody had the experience with this novel virus,” he says. “And part of it was that it came into the community at a time when people were still convening, before social distancing was a household term. No one had a mask, except medical professionals. It was just an environment that was primed for a disaster.”

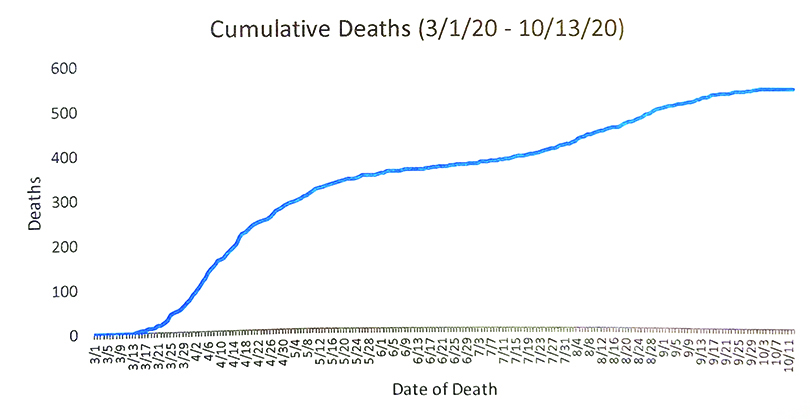

The Dougherty County coroner, who Ruis says he didn’t know that well before the pandemic, was calling him every day. “He would tell me, we just picked up another one,” he says. “Many people were dying at home because the clinicians in town, and throughout the world really, had to learn a new disease. Some people were not going to get checked. A few people had gone to get checked and they appeared to be very stable, thinking they had a cold or maybe even the flu, and I’m sure they were. But what we discovered is people would go home and do OK for a few days and then suddenly rapidly decline.”

Many deaths couldn’t be immediately identified as COVID-19-related because turnaround times for test results were so long, making it even more difficult to contain the spread.

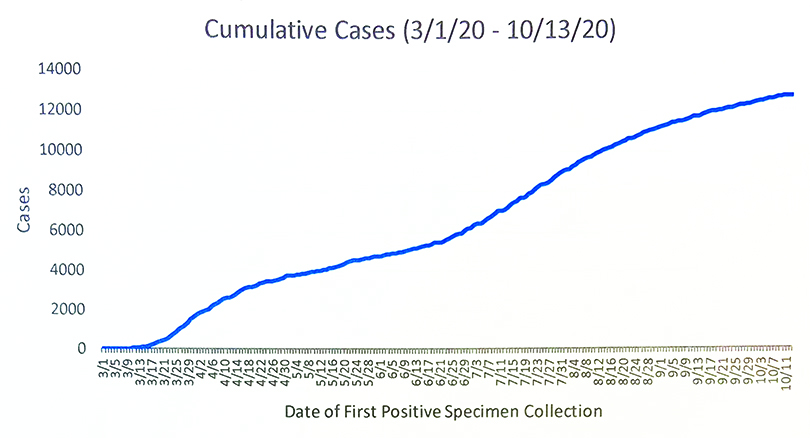

We very quickly realized we weren’t prepared,” Ruis says. “Once it started here, there was no pullback for months. Every day was just more and more intense. I started a list of those who had died from COVID and it just grew exponentially. It wasn’t long before I abandoned that and left it to our epidemiologists.”

The knowledge pool

The knowledge pool

For the first few weeks of the pandemic, Ruis says public health’s main role became delivering what PPE they did have and other COVID-related supplies to hospitals and long-term care facilities throughout the area that were quickly running out.

In late March an outbreak at Dawson Health and Rehabilitation in neighboring Terrell County and another at Pelham Parkway Nursing Home in nearby Mitchell County broadened their scope. “Very quickly, our role evolved into infection control education,” he says.

Nursing homes and other long-term care facilities combine numerous risk factors for transmission: communal living, a mostly elderly population with underlying health conditions and sometimes inadequate staffing and no stockpiles of PPE, which makes them primed for spread of disease.

Along with teams from Georgia’s State Office of Public Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Ruis and his team began visiting area facilities with supplies of PPE to talk about proper handwashing, gloving, gowning and mask-wearing.

“It was a solemn, almost depressing occasion, because I can still see the fear in their faces,” he remembers. “They went to work every day knowing they were putting themselves at risk and possibly their families at risk. I have tremendous admiration for them.”

Ruis also had a responsibility to educate the public. During the first weeks of the outbreak, he remembers giving television and radio interviews nearly every day, sharing what little information they had.

“The universal knowledge fund on COVID was still very small, but we passed on what we knew trying to keep the public as calm as we could,” he says. “Our role is to pass on objective information, what the dangers and risks are, but at the same time help them be cognizant of what we can do to avoid bad outcomes and to find comfort in the knowledge we have and the medical interventions we have.”

Changing roles again

Changing roles again

As the virus continued to spread through the community and the state, more people wanted and needed to be tested: Phoebe was bearing the brunt of that testing.

“The idea then was that public health probably wouldn’t need to be involved, but that quickly changed,” Ruis says.

In the early days, test kits were extremely hard to come by, so they tested the most vulnerable — the elderly and people with underlying health conditions. Turnaround times for results were slow, sometimes taking up to 7 days, and without a positive result, infected, but asymptomatic people were unaware of their need to isolate, potentially contributing to the spread.

As more kits eventually became available, public health also stepped up to provide more widespread testing, setting up mobile sites across the community.

It was grueling work, a lot of it done outdoors in the South Georgia heat and humidity.

“Our employees endured some grueling conditions for hours at the time,” Ruis says. “Temps in the 90s, humidity, wearing PPE head to toe.”

At the height they were performing 600 tests a day.

“I’m proud to say we performed over 50,000 tests outdoors, and while we had a few people who overdid it in the heat, nothing was too serious. I am unaware of any employees who developed COVID-19 as a result of testing the public,” he says.

Tracking down cases

Another way public health worked to slow the spread was by making sure people who did contract COVID-19 stayed in isolation, tracking down others who may have been exposed and encouraging them to quarantine and get tested.

The Southwest District’s epidemiology staff normally consists of about three people who deal with communicable diseases and in the first few weeks of the pandemic, they were able to handle the workload.

That didn’t last long.

“At that time, even the CDC was saying that we would probably reach a point when we wouldn’t be able to do all the case investigations and the contact tracing and we’d just have to mitigate,” Ruis remembers.

To try and keep up, staff were repurposed and temporary workers hired. Some nonessential public health services, like immunization clinics and some women’s clinics, had to be put on hold. Staff racked up hours and hours of overtime, working nights and weekends.

“At one point, all of our RNs were involved in case investigations,” Ruis says. “They are hard-working, dedicated and compassionate people, but they were getting worn kind of thin.”

Finally in May, the state announced they would recruit and hire new staff solely dedicated to contact tracing and case investigations. Hundreds were hired, about 50 of those going to the Southwest District.

By the fall, that staff was still sending texts and calling an average of 500 people in the district still in quarantine.

The way forward

As the number of COVID-19 cases in Southwest Georgia began to wane mid-summer, public health needed to get back to business.

“This pandemic pretty quickly shed a light on the susceptibility of vulnerable populations,” he says.

The most important job in public health is figuring out how to make vulnerable populations less so, Ruis says. What can be done to help people better manage chronic diseases? How can we improve people’s access to care? How can we improve people’s living and working conditions?

“Public health has a role in being a voice and a force to ensure changes occur.”