John West, ’85, was saved thanks to the friendship of two MCG graduates

The story begins more than 120 years ago, when Robert M. West Sr. graduated from the Medical College of Virginia in May 1900. Or maybe it begins when Robert M. West Jr. — Bob — earned his degree from the Medical College of Georgia in June 1955.

Or maybe not.

John — Bob’s son and Robert’s grandson, who graduated from MCG in 1985 — keeps both of their diplomas on his wall.

John knows that his grandfather was a general practitioner in Salisbury, North Carolina — he has his original office ledger of daily office visits, with charges and payments including cash and also chickens, eggs and vegetables. John knows that Bob, once a professional saxophone player until he decided to follow in Robert’s footsteps, tried for four years to get into MCG; it took another seven years of part-time study for him to graduate as a general practitioner.

John West also knows this — and this is actually the real story: Had his grandfather not become a doctor, and had his father not persevered, he would not be here.

A first-born son

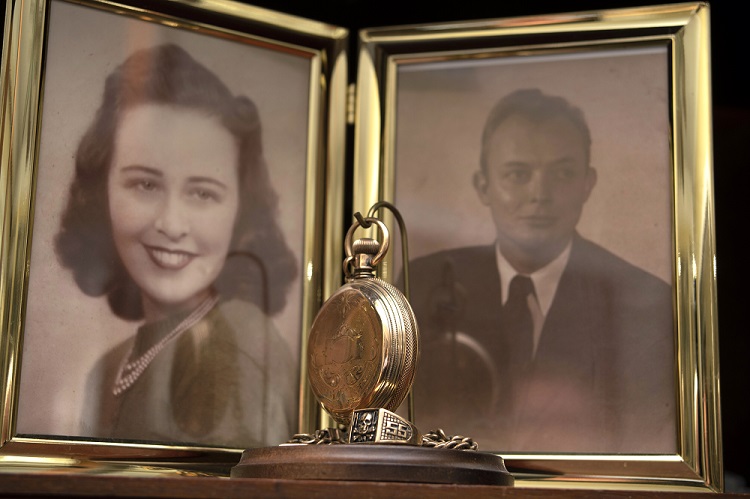

It was December 1955, and Dr. Bob West and his wife, Mary Alyce, were preparing for the Christmas holidays. Life was not perfect, but it was good: Bob was completing an internship at Atlanta’s Grady Memorial Hospital – there was no residency requirement at that time – and the couple would soon be moving to Forest Park, Georgia, to start his practice.

Then came a call from Dr. Jack Raulston, ’53, Bob’s former MCG cadaver lab partner and good friend. Raulston was an OB/GYN practicing in Palm Beach, Florida, and a pregnant woman with five other children had come into his office with a desperate request: Although abortion was illegal at the time, she wanted his help to end this unplanned pregnancy.

Raulston knew the Wests weren’t able to have children. So, he asked the mother if she would consider adoption; she said yes, and Raulston immediately put in a call.

Six months later, Mary Alyce flew to Palm Beach alone, and came back to Atlanta with a newborn baby, the Wests’ first-born son, John.

Coincidental Circumstances

West grew up knowing his story, and so did his friends — “So my adoption never became a weapon used to tease, and if they tried it, I had one great comeback: ‘My parents had to go get me, so they really wanted me.’ … it was never thought to be a shameful thing.”

West also knew all the other family stories. Bob used to ride with his own father in a horse and buggy to call on patients. After playing saxophone with big bands for a time, Bob started studying to be a doctor, but had to start his dream all over again when the medical college at Atlanta’s Oglethorpe University was disaccredited and closed. Then, his MCG application kept getting blocked by one faculty member who didn’t believe he had the aptitude for medicine.

Bob and Mary Alyce worked to save money — Bob as a research assistant for Dr. Robert Greenblatt, internationally known for his work in reproductive endocrinology, while Mary Alyce was a secretary for Dr. Hoke Wammock, ’28, who established MCG’s then Department of Oncology — while he kept applying, until he finally was accepted. Then, over the next seven years as Bob attended MCG part-time, he was shoulder to shoulder with the giants — Greenblatt and Wammock, along with G. Lombard Kelly, president of MCG from 1950-53; Edgar Pund, chair of the Department of Pathology who was named president in 1953; and others.

West drank it all in, including the fact that Bob graduated with honors and was a member of the Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society. So, it didn’t seem at all surprising for him at age 5 to declare to his Pop, “I want to be a doctor just like you.”

Three years later, West was going on house calls with Bob, just as Bob had done with his father. At 10, he was helping in the office, whether that was handing him instruments, sterilizing equipment, or wrapping sutures. Bob would even often wake West when he had an emergency call as the company doctor for Georgia Power, American Can and Crown, Cork, and Seal, or in response to a car accident or other situations. The scenes could be traumatic, “but those situations helped shape who I would become,” says West. “And at that young age, I knew that each incident was a learning experience.”

After high school, West decided to attend the University of Georgia — the fact that he was dating his future wife, Lee, his high-school sweetheart, had more than a little to do with it. The choice of medical school was even easier: “Pop had a lot to do with that,” he says. “I don’t recall applying anywhere else [but MCG].”

He was finishing up his last requirements for graduating UGA and had completed an interview for MCG when the first rejection letter came. He wasn’t going to give up, but in the meantime, joined the Georgia Department of Human Resources in downtown Atlanta as a senior laboratory scientist in the virology lab. Every day after work, he’d stroll two blocks to Georgia State University, where he was taking graduate-level courses at night to stay academically active. He and Lee married that fall, then a month later he walked up to the sign-in table at UGA to retake the MCAT when he stopped and walked right back out. “I knew with everything going on and us getting married, I hadn’t spent any additional time trying to study or to improve,” he says. “At that moment, I had the awareness that if I took the MCAT again and did worse, it would worsen my chances.”

He applied again based on his original MCAT scores — then was rejected outright, without even an interview.

Remembering how Bob hadn’t given up, West took the day off from work to drive the nearly three hours to Augusta. He walked into the student center and into the office of Dr. Jim Puryear, then director of student affairs, and asked to speak with him. As West had no appointment, Puryear’s secretary said, “You’ll have to wait.” “So I sat down in his outer office and waited,” says West. “My knowledge of Pop’s experience and perseverance to become a physician had taught me that you have to work for what you want and not to let anyone else tell you that you were not good enough to do it. I was not going to leave until I had talked to this person.”

He waited from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. — the secretary took pity on him and gave him a lunch ticket to the downstairs cafeteria — until Puryear finally was available. West had one question ready: “What do I need to do to get into MCG?”

There was more waiting as Puryear pulled out a file on West and flipped through it. “I remember him as a matter-of-fact, but kind person,” says West. “He looked over everything, he didn’t dissuade me…but he matter-of-factly said, ‘You need better numbers.’” So West responded, “OK, I’ll get them and I’ll be back.”

The meeting took all of 10 minutes. But West had his marching orders. For the next eight months, he studied for 2.5 hours a day — during breaks at the lab, with permission from his manager — while continuing to work full-time and take night classes. He retook the MCATs and raised all of his scores, including doubling his physics score, and reapplied with high hopes.

Then it was February, and friends were getting acceptances, but not West. Finally, the invitation for an interview came, but in June, another letter: He was an alternate. Lee was worried, so as a backup plan, West applied and was accepted to UGA’s landscape architect school. It wasn’t as out of left field as it might seem: He enjoyed building and nature, and his next-door neighbor growing up was a landscape architect.

Then late summer, after he came home, Lee greeted him with shining eyes. In her hands was a registered letter. “Back then, you knew that you were going to be accepted because the letter came by registered mail,” West says. It was signed by Dr. Puryear.

He and Lee immediately drove the 15 miles to Forest Park, where Bob and Mary Alyce still lived. “I walked in and handed him the letter, and he got all teary,” says West. Bob passed away in 1997 at age 82, an MCG-trained physician for 41 years. But in West’s mind’s eye, “I can still see him… He didn’t say anything, just hugged me and cried.”

Three Lifetimes

“To me, it was a lifetime of preparing [to be a doctor],” says West. Or, even three lifetimes, thinking back to not just his father but also his grandfather, three generations of physicians.

It was also due to MCG, which connected Bob to Jack Raulston and saved West.

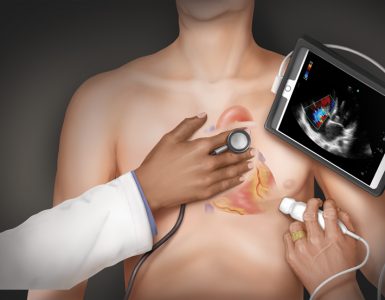

What he appreciates most about his time at MCG is the medical school’s training philosophy: “The people who trained and taught me always did so in a way that I always felt they were there to help me be the best,” he says. “They wanted you to go out with confidence.” After graduating and completing his internship and family medicine residency at MCG, West opened a private practice in family medicine in 1988; today, he’s still seeing patients, having just opened a new practice with Atlanta’s Northside Gwinnett Hospital. In addition to family medicine, West has also been board certified in clinical lipidology since 2008, and his practice now involves adult medicine with an emphasis on adult primary care and prevention, focusing particularly on atherosclerotic coronary artery disease prevention and aggressive treatment of lipid and lipoprotein disorders. In more than three decades of medical care, West has received multiple awards, including being named 2017 Physician of the Year by the Gwinnett County Chamber of Commerce for his work in lipidology for coronary artery disease prevention and treatment.

“I was saved. I never took that for granted. There are [patients] I’ve seen whose lives I’ve saved. Had I not been here to begin with, that might not have happened. I have tried to give something back every day to honor the fact that I am here. If not for two MCG grads, I would not be here today.”

–Dr. John West